NOVA Wonders What's the Universe Made Of?

Season 45 Episode 106 | 53m 10sVideo has Closed Captions

Peer into the deep unknowns of the universe to explore its mysteries.

The universe is hiding something. In fact, it is hiding a lot. Everything we experience on Earth, the stars and galaxies we see in the cosmos—all the “normal” matter and energy that we understand—make up only 5% of the known universe. Find out how scientists are discovering new secrets about the history of the universe, and why they’re predicting a shocking future.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

National corporate funding for NOVA Wonders is provided by Draper. Major funding for NOVA Wonders is provided by National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Alfred P....

NOVA Wonders What's the Universe Made Of?

Season 45 Episode 106 | 53m 10sVideo has Closed Captions

The universe is hiding something. In fact, it is hiding a lot. Everything we experience on Earth, the stars and galaxies we see in the cosmos—all the “normal” matter and energy that we understand—make up only 5% of the known universe. Find out how scientists are discovering new secrets about the history of the universe, and why they’re predicting a shocking future.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipTALITHIA WILLIAMS: What do you wonder about?

MAN: The unknown.

What our place in the universe is.

Artificial intelligence.

Hello.

Look at this, what's this?

Animals.

An egg.

Your brain.

RANA EL KALIOUBY: Life on a faraway planet.

WILLIAMS: "NOVA Wonders"-- investigating the biggest mysteries.

We have no idea what's going on there.

These planets in the middle we think are in the habitable zone.

WILLIAMS: And making incredible discoveries.

WOMAN: Trying to understand their behavior, their life, everything that goes on here.

MAN: Building an artificial intelligence is going to be the crowning achievement of humanity.

WILLIAMS: We're three scientists exploring the frontiers of human knowledge.

ANDRÉ FENTON: I'm a neuroscientist and I study the biology of memory.

EL KALIOUBY: I'm a computer scientist and I build technology that can read human emotions.

WILLIAMS: And I'm a mathematician, using big data to understand our modern world.

And we're tackling the biggest questions...

Dark energy?

ALL: Dark energy?

WILLIAMS: Of life... DAVID PRIDE: There's all of these microbes, and we just don't know what they are.

WILLIAMS: And the cosmos.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: On this episode... ALEX FILIPPENKO: Hey, it's there!

We got something!

WOMAN: The first-- ever.

WILLIAMS: The hunt for the secret ingredients of the universe.

FLIP TANEDO: This was a mystery.

SAUL PERLMUTTER: We came up with this bizarre result.

DAVID KAISER: Most of what astronomers had assumed about our universe fell apart.

(explosion) WILLIAMS: The mysterious, invisible forces that control the fate of the cosmos.

FILIPPENKO: It's 70% of the contents of the universe.

MARCELLE SAURES-SANTOS: We have no idea what it is.

Very weird!

I mean, it's crazyland!

WILLIAMS: "NOVA Wonders"-- "What's the Universe Made of?"

Right now.

Major funding for "NOVA Wonders" is provided by... WILLIAMS: When you stare up at the sky at night, it's hard not to wonder, what's out there in the cosmos?

Today we can see incredible things.

Telescopes gaze at galaxies far, far away.

And we've peered back in time almost to the beginning of the universe itself.

But in recent years, astronomers made a disturbing discovery: our universe is hiding something.

Actually it's hiding a lot.

EL KALIOUBY: It turns out, all the stuff we can see, all that we've come to understand, adds up to only 5% of the universe.

The other 95% is made up of two mysterious ingredients.

Dark matter and dark energy.

Not only do they make up most of the cosmos, but the two are in an epic battle to control the fate of the universe.

(explosion) FENTON: Today, scientists are on the hunt, trying to understand these dark mysteries.

WILLIAMS: Uncovering new secrets about the history of our universe and predicting a shocking future.

I'm André Fenton.

I'm Rana El Kaliouby.

I'm Talithia Williams.

And on this episode, "NOVA Wonders"-- "What's the Universe Made of?"

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ (phone vibrating) I think it was 7:40 in the morning, my phone rings, and my colleague says, "Wake up!"

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: Early on an August morning, at her apartment in Chicago, Marcelle Soares-Santos gets the call she and dozens of other astrophysicists have been waiting for.

SOARES-SANTOS: My colleague says, "We received a signal.

We have to take action."

And I'm like, "Oh!

This-this is really happening."

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: The signal is of vibrations created by a gigantic explosion across the cosmos.

We are talking about two neutron stars.

WILLIAMS: 130 million light years away, two massive neutron stars have violently crashed together.

SOARES-SANTOS: Very dense objects colliding at approximately the speed of light.

(explosion) The explosion is gigantic, it's tremendous.

WILLIAMS: Astronomers around the globe rush to their telescopes, hoping to capture the faint light of this distant catastrophe.

On a mountaintop in Chile, some of Marcelle's colleagues point a powerful telescope toward a patch of sky in the constellation Hydra.

SOARES-SANTOS: We expect the light from these sources to fade away quickly, so you have to act fast.

♪ ♪ WOMAN: The data taking has started.

WILLIAMS: As the pictures come in, researchers all over the world sift through the data looking for one extraordinary dot.

The sky is full of beautiful, bright sources, but there will be one that was not there before that is there now.

WILLIAMS: Finally... Holy (bleep), look at that.

WILLIAMS: ...someone spots something.

That blob here.

WILLIAMS: Very low on the horizon, there's a light in the sky... We found it!

WILLIAMS: ...that has never been seen before.

MAN: That really small spot of light.

MAN 2: That one, right there.

Very, very cool.

It's spectacular!

You don't get many chances like that.

Yeah.

Looking at the screen, and you're like, "Is this really happening?

Is this real?"

(explosion) ♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: This tiny blob is the light from that titanic collision in a galaxy far away.

♪ ♪ Not only is this the first time such an event has been captured, but for Marcelle and her colleagues, this kind of data could help solve a mystery that's perplexed astronomers for years-- to decipher the strange, invisible ingredients that make up the vast majority of our universe.

♪ ♪ But the clues to solve this mystery aren't just in galaxies deep in space...

They could be all around us.

In a remote Canadian forest just north of Lake Huron, another group of scientists is setting a trap.

But their snare is not aimed at the sky... (metal rattling, radio chatter) ...it lies in the other direction.

Deep beneath the forest is the Vale nickel and copper mine.

(metal clanging) KEN CLARK: So we're about 6,800 feet underground.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: For more than a century, miners here have pulled metal ore out from the surrounding rock, but now another team has come.

CLARK: We're down here in this mine, because it shields out all the radiation that would make our detectors unusable on surface.

WILLIAMS: Ken Clark is a different kind of miner, seeking a treasure far more precious.

(metal clanging, machinery humming) That noise is the ventilation doors, it effectively creates an airlock.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: These machines are designed to detect a very elusive particle.

CLARK: It doesn't interact with light, we can't see it.

But the discovery really could be just around the corner.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: Ken is one of dozens of scientists here hunting a substance so mysterious it doesn't even have a name.

They call it dark matter.

CLARK: There's a lot of experiments, we're all kind of racing to try and find this thing.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: Racing to find it, because scientists believe this mysterious stuff played a key role in shaping the universe as we know it.

Ken and Marcelle are just two in a long line of cosmic detectives trying to understand how our universe works and what it's made of.

It's an investigation that's revealed bigger and bigger surprises, starting about a hundred years ago.

Back then, most scientists-- even Albert Einstein-- thought that the entire universe consisted only of this-- a single galaxy, the Milky Way, sitting in space.

But this small, simple universe was about to be blown to smithereens.

(explosion) The telescopes back then were small, but besides stars, they could make out faint glowing clouds, which scientists believed were made of gas and dust.

They called them nebulae.

One scientist, Edwin Hubble, decided to take a closer look.

PRIYAMVADA NATARAJAN: What Hubble needed to do was to actually measure the distance to these nebulae.

WILLIAMS: Using one of the most powerful telescopes of the day, Hubble was able to pick out stars in these nebulae and calculate their distances.

To his amazement, he found that they were over four times farther away from us than any star seen before in our Milky Way.

KAISER: The distances from us were truly astronomical.

These nebulae, they weren't just smears of gas, they were indeed collection of stars all their own outside of our galaxy.

WILLIAMS: Hubble realized that this nebula-- known as Andromeda-- wasn't a cloud of gas at all, it was another galaxy.

And it wasn't the only one.

♪ ♪ KAISER: We learned that the Milky Way Galaxy is one of a vast sea of galaxies, hundreds of billions-- maybe more!

Galaxy, after galaxy, after galaxy in every direction-- down, up, sideways, in an infinite universe.

WILLIAMS: What's more, Hubble, along with other astronomers, could see these galaxies were on the move, rapidly flying away from us.

Hubble found that the universe isn't static after all.

It's expanding.

KAISER: Most of what astronomers had assumed about our universe fell apart.

KATHERINE FREESE: It was a complete paradigm shift, it was a complete shock to everybody.

Pretty disorienting.

WILLIAMS: Far from being confined to a single galaxy-- the Milky Way-- the universe was filled with galaxies, and they were all on the move.

Hubble's discovery means that the universe is big-- and getting bigger all the time-- with galaxies flying away from each other.

But if that's true, if everything in the universe is flying apart right now, what did it do in the past?

What would happen if you ran the clock backwards?

(button clicks, stopwatch ticking) TANEDO: Essentially, what we're doing, is we're playing the tape backwards, and we're saying, "If the universe is getting bigger now "it must have been small earlier.

It must have been really, really small a long time ago."

(ticking) WILLIAMS: Keep rewinding, and everything gets closer and closer together.

Eventually, they get so dense that you have a soup of elementary particles.

All the stuff we see around us was compacted to literally a single point.

All of space was a little tiny dot.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: This is how it all started.

We don't necessarily know why it started that way, but it started out as this very, very small region of high density.

(clicks, explosion) WILLIAMS: The Big Bang.

(ticking) As the clock ticks forward now, in the very first fraction of a fraction of a second, scientists think the universe went through an intense period of expansion.

We call that era Cosmic Inflation.

BRIAN NORD: The initial stages are like a growth spurt.

So there's this period of inflation, where the universe's size grew really, really fast.

Ripping apart at an enormous, enormous, exponential rate.

(explosion) WILLIAMS: As it cools, the growing universe condenses into a soup of exotic particles.

The universe is a hot, dense, plasma.

It's a hot gas.

There's particles, there's anti-particles.

They're coming in and out of existence.

WILLIAMS: The seconds tick by, the soup of particles remains unsettled.

380,000 years pass by.

As the universe keeps expanding, it cools.

MELISSA FRANKLIN: Then you get atoms, because things are cooling enough that atoms can actually form where you have protons and neutrons in the center, and electrons around them.

KAISER: For the first time in cosmic history, the temperature falls just low enough, and that changes things forever.

(explosion) WILLIAMS: Finally, light can travel across space.

This is a snapshot of that moment-- a baby picture of the universe.

An image of the universe when it was just an infant.

380,000 years after the Big Bang.

Now that may sound like a long time on a human time scale, but compared with the age of the universe, 13.8 billion years, it's just an instant near the very beginning.

WILLIAMS: Already, the blue areas reveal where matter will clump together, forming the seeds that will grow into galaxies.

The first stars are born, and die, and re-form in a cycle generating the building blocks for planets, ever more complex chemistry, and, eventually, us.

♪ ♪ But why did galaxies begin to form at all?

The energy that was expanding the universe ever since the Big Bang should have spread the little bits of matter too thin.

So as the universe continues to expand, we might have expected these little tiny lumps in the universe to really get smoothed out.

Instead, we know the opposite happened.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: How could so much of the matter clump together to form the major structures of the universe?

It's a question that's plagued astronomers for decades.

♪ ♪ The first clue came from a Swiss astronomer named Fritz Zwicky, just a few years after the discoveries that had suggested the Big Bang.

Zwicky noticed that these newly discovered galaxies were behaving oddly.

FILIPPENKO: Fritz Zwicky looked at clusters of galaxies and found that the individual galaxies within those clusters are moving so fast, that the clusters should fly apart.

Moving around so rapidly, that it was impossible to understand why they didn't just wander away.

Something clearly held them in these orbits.

WILLIAMS: Zwicky could see nothing in his telescope to explain it, so he called the phenomenon "dunkle materie," translated as "dark matter," and then the idea promptly faded away.

Zwicky's observation might have ended up forgotten.

And for nearly 40 years, it was.

Until an astronomer named Vera Rubin entered the field.

TANEDO: Vera Rubin was one of these astronomers who was not appreciated until much later.

She was a woman in astronomy at a time when the field was not particularly friendly to women.

Rubin chose to work in a relatively quiet area of astronomy, making straightforward measurements of stars as they orbited in their galaxies.

Here's what we get.

WILLIAMS: But she too noticed something bizarre happening.

The stars way out here are going very fast.

WILLIAMS: The stars at the edge of the galaxies were moving so fast that they should have been flung off into space.

TANEDO: This was a mystery that these stars were moving too fast to be explained by ordinary matter.

♪ ♪ Think about a spinning wheel, covered in water.

If the wheel is moving slowly, the water clings to the wheel.

But spin it fast enough... ♪ ♪ The water flies off.

The same thing should happen out in the universe.

Stars swirling around in a galaxy-- if they orbit too fast, they'll get flung off, out into space.

Except that's not what Vera Rubin sees.

WILLIAMS: The galaxies are spinning fast, but the stars stay in their orbits.

What's holding them there?

It has to be gravity.

...response, gravitational pull from something that's not bright.

And we don't know what that is.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: But gravity doesn't exist alone, it depends on stuff-- matter and energy.

Vera Rubin knew that gravity is produced by mass.

Einstein had proven it.

KAISER: The main takeaway message of Einstein's general theory of relativity is that gravity is nothing but the warping of space and time.

Space-time itself becomes something like a fabric that when we put objects like galaxies within this fabric of space-time, it will warp.

WILLIAMS: Massive objects create hills and valleys in the fabric of space, and these create gravity.

The one thing that we know, is that if you have stuff with mass, stuff with energy, it's going to pull planets.

It's going to pull stars.

It's going to pull other galaxies.

WILLIAMS: The amount of gravity all depends on the amount of mass.

The more stuff rolling around in the fabric of space, the more distortion, the more gravity.

It was clear to Vera Rubin that a lot of gravity was holding the stars in place, but there wasn't enough stuff-- enough visible matter-- to generate so much gravity.

There must be some missing matter.

♪ ♪ Dark matter was real.

♪ ♪ It doesn't shine, it doesn't give off light.

By definition it is the stuff that we have a really hard time being able to quantify.

That's why they called it dark matter.

The more astronomers looked, the more dark matter there seemed to be.

But how much is there?

And where exactly is all this mysterious stuff?

♪ ♪ Astrophysicist Priya Natarajan is trying to find out.

NATARAJAN: I have worked my entire career on trying to understand the nature of dark matter.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: But how do you understand what you can't see?

Luckily, this invisible dark matter gives itself away because it has a habit of playing tricks with light.

(beeping) NATARAJAN: In 2014, with the Hubble Space Telescope, a very intriguing kind of object was observed.

WILLIAMS: It appeared to be a galaxy with four exploding stars, called supernovae, going off at the same time.

Like four evenly-spaced supernovae.

WILLIAMS: In reality, there's only one supernova.

But it somehow shows up in four different places.

What's going on?

This configuration of four evenly-spaced multiple images is called an Einstein Cross.

It was predicted by Einstein.

In reality, one supernova went, "Whoop," and we had a little gift.

♪ ♪ The paths of light rays are bent into a configuration with four distinct images of the same supernova.

WILLIAMS: Somehow the light from that one supernova traveled along several bending pathways, arriving at four different spots in the sky.

NATARAJAN: The phenomenon of light bending is something we actually encounter every day and it's all around us.

So, for example, if you look at, say, graph paper through the bottom of a wine glass, you know this is a regularly spaced grid, but because of the light bending, you can actually see a stretching of the grid pattern.

WILLIAMS: In the cosmos, what bends light is gravity distorting the fabric of space.

It's called gravitational lensing, and it can produce spectacular results-- smears, rings, smiley faces.

It can even make a supernova show up in four different places at once.

For Priya, these aren't just fascinating illusions.

They are crucial clues in the dark matter mystery.

Since gravity is what bends the light in these images, and dark matter creates gravity, the distortions can reveal where dark matter is in the universe.

NATARAJAN: And so it's the dark matter that is producing this huge amount of distortion.

WILLIAMS: So Priya is gathering a giant database of these distortions, all in her quest to map out dark matter throughout the universe.

(beeping) And Priya and maps?

Well, they go a long way back.

NATARAJAN: We're going to one of my favorite places, where I fulfill all of my childhood fantasies.

The map room at the Beinecke Rare Book Library.

WILLIAMS: Priya's quest grew from an obsession that's gripped her since she was a young girl.

I was obsessed with all kinds of maps and atlases when I was young.

I'm-I'm.... like, I'm crazy about maps.

♪ ♪ It's beautiful.

♪ ♪ These mappers of yore, when they ran out of data or knowledge, it was marked as "terra incognita"-- mythical places that await exploration.

WILLIAMS: The places that young Priya most wanted to map were not on earth, but in the heavens.

There was something about the cosmos being a little bit out of reach that really attracted me.

WILLIAMS: As soon as she got her first computer, she used it to create a star chart.

It was a hard problem, and I sat down for six weeks, and I wrote the program.

♪ ♪ These were not things that no one had figured out before, right?

But I was figuring them out for the first time.

I was hooked.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: Today, Priya is fulfilling her dream of exploring the frontiers of the universe.

She's one of several researchers writing computer programs that use gravitational lensing to map the location of dark matter.

This is one of the largest maps of dark matter.

(computer mouse clicks) The red regions are where you have an excess of dark matter.

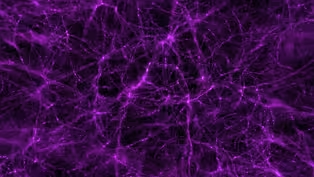

If we zoom into a dark matter simulation, it looks rather like these fibers, almost like neurons.

WILLIAMS: Using computer simulations of the early universe, astronomers now think that dark matter formed a giant web.

Where the dark matter filaments cross, at these nodes, you form these clusters of galaxies.

WILLIAMS: Astrophysicists now realize dark matter must have played a central role early on, drawing together ordinary matter and allowing galaxies to form.

We wouldn't be here if it weren't for the powerful pull of dark matter.

NATARAJAN: Our current understanding of dark matter is literally it shapes the universe that we see.

WILLIAMS: And what's clear-- there's a ton of it.

By now we actually have many independent measures, many independent ways to estimate the total amount of dark matter in the universe.

And, amazingly, each of them points to an amount of something like five or five to six times more dark matter than ordinary matter.

For every atom of ordinary matter, there seems to be five times more mass in some mysterious dark matter throughout the entire universe.

Let's say I'm made of ordinary matter, the stuff we see and understand, like atoms.

Now add dark matter, and it's as if for every one of me, the universe has about five more, made of entirely different stuff.

They're there, but completely invisible.

We only know they exist because of their gravity.

It seems totally bizarre and kind of freaky, yet that's what the universe is telling us.

The vast majority of matter is this mysterious stuff, dark matter.

But what is it?

I can't imagine that dark matter is fire-breathing dragons that will come out of black holes to eat us.

It's definitely not that.

But could it be a heavy particle?

Could it be a light particle?

Can it do exotic things?

Maybe it's something really boring.

I don't know.

WILLIAMS: These kinds of questions are nothing new.

People have been wondering about what exactly matter is for millennia.

But only recently have we had the tools to actually figure it out.

A hundred years ago, in a sense, all matter was dark matter, because we didn't have the technology to pull apart what these particles are that everything is made out of.

WILLIAMS: In the early 20th century, while Hubble was peering up at the cosmos, other scientists were focused on the tiny world of atoms, trying to decipher the nature of matter itself.

They devised enormous machines, called accelerators, to break atoms into their constituent parts.

♪ ♪ Accelerators revealed a zoo of elementary particles with all sorts of whimsical names.

LYKKEN: Particle names, some of them are cute, like neutrino, which I think is one of the best names.

Quarks.

You have up and down quarks.

Top quark.

Bottom quark.

Charmed and strange quarks, and truth and... Beauty quark.

Gluino.

Electron.

Photino.

Photons.

Gluons.

Pion.

Kaons.

Upsilons.

The Higgs-Boson.

Oh, positron actually.

Positron is great.

Yeah.

♪ ♪ Through decades of experiments, physicists have figured out so many recipes describing what the universe is made of at the tiniest of scales.

Groups of quarks make a proton.

Protons, neutrons and electrons make atoms.

Atoms combine to make molecules.

Together, they make the stuff we know and love.

Today, the biggest particle accelerator is at CERN, near Geneva, Switzerland, where physicists recently detected a new particle, the Higgs-Boson, which gives normal matter its mass, and they're still looking for more.

The question is: is dark matter anything like ordinary matter?

Is dark matter some other kind of particle we just haven't detected, haven't found yet?

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: The answer must lie at the intersection of particle physics and astronomy.

♪ ♪ Peter Fisher was one of the first to bring particle physics to the dark matter problem.

♪ ♪ PETER FISHER: Finding out what dark matter is has been something that's really driven more by particle physics than by astronomers.

WILLIAMS: For decades, physicists like Peter have focused on a theoretical particle called a "WIMP."

Weakly Interacting Massive Particle-- or WIMP.

I think there was a lot of work that went into finding that acronym.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: In order to create the kind of gravity that draws large amounts of matter together, the particle would need to have mass, but because it's invisible and eludes detection, it also must be "weakly interacting."

FISHER: So I think of dark matter as kind of ghosts.

We don't see them because they just don't interact very often.

What that means is that a WIMP could pass right through the earth, without hitting any of the atoms in the earth.

In fact, if you lined up a hundred billion Earths, a WIMP would go right through.

WILLIAMS: So how do you capture such an elusive particle?

♪ ♪ Peter Fisher spent 20 years building machine after machine, attempting to do just that.

♪ ♪ My students, postdocs and I have built hundreds of these different experiments.

Hundreds!

There's the remnants of three sitting right here.

This is really kind of a mess.

Every experiment we build is bigger and more complicated.

WILLIAMS: And with each generation, the experiments not only got larger and more complex, they went further underground.

♪ ♪ The hunt for WIMPs brought particle physicist Ken Clark here to this mine in Canada.

CLARK: We try to detect them in a much more physical way.

We're actually looking for this dark matter to interact.

And that's what most of the major dark matter experiments right now are trying to do.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: There are four different experiments at Snolab.

At 6,800 feet underground, it is one of the deepest labs in the world.

It has to be.

CLARK: All the time, all around us there is cosmic rays and there's particles that are streaming in through the earth's atmosphere, and that kind of thing.

If we were to set up our experiments here on the surface, we would be completely swamped by those signals.

WILLIAMS: Instead, the experiments are brought here, a mile underground, into special caverns blasted out of the bedrock.

♪ ♪ The laboratory functions as one giant clean room, to keep the experiments free from interference.

CLARK: One fingerprint on the experiment would make it unusable.

It would be too dirty for us to actually use.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: The largest of the caverns down here houses the DEAP 3600 experiment.

It's the biggest liquid argon dark matter detector currently in operation.

So this is our cryo coolers right now.

They keep the temperature at -200 degrees Celsius in the detector.

WILLIAMS: Inside this huge vat is the liquified gas argon.

It has to be kept extremely cold-- almost at absolute zero.

Inside, the idea is that the argon atoms are so cold they are barely moving.

If any foreign particle were to fly through the argon, even if it were weakly interacting, it might hit one of the argon atoms, setting off a chain reaction and trigger a detection.

♪ ♪ So far, the huge ultra-cold experiments have yet to yield any dark matter.

The dark matter from outer space so far has been missing.

None.

(chuckles) WILLIAMS: Just down the hall, Ken Clark's experiment takes a slightly different approach.

He's not freezing things, he's looking for them to boil.

The experiment starts with a container full of superheated liquid made of carbon and fluorine.

It's placed under high pressure to keep it from boiling.

Which means it's at a temperature above its normal boiling point at this pressure, so any little deposit of energy means it boils instantly.

WILLIAMS: Under these conditions, if a particle enters the liquid from outside, it could immediately push the liquid past the boiling point.

We're looking for the dark matter particle to come in, hit one of the fluorine nuclei, cause it to recoil that tiny bit, and then cause a bubble in here.

WILLIAMS: Custom-designed cameras are constantly filming... waiting for a bubble, but they haven't found a WIMP yet.

CLARK: So far, this one has detected exactly zero dark matter particles.

But we're hopeful that the next generation we're going to actually see something in it.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: Back at M.I.T., it's a familiar story for Peter Fisher.

FISHER: In hundreds of experiments we've never seen what we know to be a WIMP.

♪ ♪ I've been doing this for 35 years, and so you might think that not having detected a WIMP, I would be frustrated by that.

Maybe a little bit, but as a scientist, what's exciting is building something and seeing it work.

Someday these ideas might really shape how we think of ourselves as-as living beings.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: We may not yet know what dark matter consists of, but we do know what it's been doing.

♪ ♪ Ever since the Big Bang, (explosion) dark matter's gravity has been drawing the universe together.

Once astronomers realized this, they began to wonder what this might mean for the future.

KAISER: We know the universe is filled with ordinary matter.

It's chock full of dark matter.

The gravitational tug of all that matter should have sort of slowed the rate at which the universe as a whole continued to expand.

Maybe the expansion itself could literally halt, maybe even leading to a reverse Big Bang-- the Big Crunch.

Think about the simple act of throwing a ball.

Every time I throw the ball up, gravity will slow it down, and at some point, will pull it... back to earth.

So could this happen to all the stuff in the universe?

We know that everything in the universe is flying outward right now, but how long will that last?

Could it be like this ball?

Slowing down, eventually reversing direction, and returning to where it came from.

What would that mean for the future of the universe?

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: In the late 1990s, two groups of astronomers-- including Saul Perlmutter and Alex Filippenko... 8.83 arc seconds north.

WILLIAMS: ...were trying to answer that very question: as the universe was expanding, would gravity slow it down, and eventually pull it back together?

FILIPPENKO: The original goal of our project was to measure the rate at which the expansion of the universe is slowing down.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: They set out to measure the speed of the universe as it expands outward and detect how much it's slowing down.

But how do you do that?

Turns out, there's a kind of star that's perfect for this measurement-- a supernova.

Yeah, right there.

Oh yeah, it might be right there.

FILIPPENKO: A supernova is simply an exploding star.

Now most stars, like our sun, will die a relatively quiet death, but a small minority literally destroy themselves in a titanic explosion at the end of their lives, becoming millions or even several billion times as powerful as our sun.

PERLMUTTER: Because they're so bright, this one object can be seen ten billion light years away and further, so already that's interesting.

WILLIAMS: The team needed a particular kind of supernova called a Type 1a.

(explosions) Their explosions always reach a certain peak brightness, allowing astronomers to calculate their distance from Earth.

Like headlights on a road, the dimmer they appear, the farther away they must be.

But first, astronomers had to find them.

Is it there or is it not?

FILIPPENKO: Supernovas are pretty rare.

Roughly once per galaxy per century, or even per several centuries.

(indistinct chatter) WILLIAMS: Astronomers had to survey thousands of galaxies at once looking for this needle in a cosmic haystack.

In five minutes, we'll know.

WILLIAMS: Months of grueling observation eventually yielded a handful of 1a supernovae.

Hey, it's there!

We got something!

WILLIAMS: From various times in the history of the universe.

Okay, let's keep on exposing.

WILLIAMS: Not only could they determine their distance, but the teams could also gauge how fast they were traveling as the universe expanded.

They did this by measuring something called "redshift."

Redshift is caused when light travels across regions of space that are expanding.

As the fabric of space stretches, so too does the wavelength of light, shifting toward the red end of the spectrum.

By analyzing the redshift of different supernovae, the teams could see how fast the universe was expanding and stretching at different times in its history.

PERLMUTTER: We ended up with a pool of some 42 supernova mapping out the history for some seven, eight billion years, to see when was it expanding faster, when was it expanding slower, and we looked to see whether it was slowing down enough to come to a halt.

Okay, here we go.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: But when they finished processing their data... MAN: I'd be a little suspicious of that one, guys.

WILLIAMS: ...something did not look right.

PERLMUTTER: When we actually finally made the measurement, we came up with this bizarre result.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: The supernovae were much farther away than they expected.

Meaning the stars and their galaxies were traveling much faster than anyone predicted.

KAISER: As they pieced these pieces of the puzzle together, the teams found, much to their own surprise, to the real tremendous surprise to the community at large, was that the universe is not slowing down in its expansion at all.

Instead, these surveys showed the universe is speeding up in its rate of expansion.

It's not just still expanding, it's expanding faster and faster over time.

WILLIAMS: The universe was not just expanding-- it was accelerating.

And that's like, oh my gosh, in a multiple choice test, that's not one of the options.

And my jaw just dropped.

FREESE: This is revolutionary.

The universe is accelerating?

(laughing): If I had a ball and it just started moving in that direction, moving faster and faster and faster, but no one was throwing it, or there was no force, that would be weird, right?

That would be weird.

WILLIAMS: Some unknown force was pushing the universe apart, challenging everything we thought we knew about the cosmos.

Scientists dubbed it dark energy, and they soon determined there was a lot of it.

It's 70% of the contents of the universe!

70%!

Seven zero.

It's far and away the largest contributing factor to all the stuff we can otherwise add up in the universe today.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: So what exactly is this weird stuff that makes up the vast majority of our universe?

In a sense, dark energy is a term that illustrates our ignorance of what's actually out there.

We don't know what it is.

♪ ♪ FRANKLIN: This is a case where it's kind of a mystery, and even hard to think about, even for normal physicists.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: One idea is that the energy comes from some undiscovered particle.

Another says our understanding of gravity is not quite right.

And then there's the most popular theory.

FILIPPENKO: Perhaps the simplest, and one which is not yet ruled out, is that the dark energy is simply the energy associated with the vacuum of space.

It's just part of space itself, it's not something in space, it's just part of what space is.

WILLIAMS: But it's a part of space that creates more space over and over again.

It almost sort of feeds on itself.

So, dark energy is what's stretching the universe at a faster and faster rate and it's literally making more space and dark energy is an energy of empty space.

So, it's made more empty space, which has in its own, more dark energy.

It's the only form of energy that we know that is capable of doing that.

To make spacetime expand faster and faster.

(laughing): It's very weird.

It's crazyland!

It's very weird!

We have no idea what is the physics underlying it.

WILLIAMS: Marcelle Soares-Santos is trying to figure out the physics behind dark energy.

Because it's really about figuring out something that we have no idea what it is.

WILLIAMS: She's part of the Dark Energy Survey-- an international research initiative.

We want to know, really, what is the precise nature of dark energy.

Okay, so redshift is .2... WILLIAMS: Josh Frieman leads one of the teams based at Fermilab outside Chicago.

The strategy is to try to track how fast the universe is accelerating as precisely as possible.

It turns out that the more precisely we can measure how fast the universe is expanding today, the better job we'll do in trying to figure out what dark energy really is.

WILLIAMS: Back in the 1990s, the discovery of dark energy was based on just a few dozen supernovae.

♪ ♪ But today, the Dark Energy Survey can do much more.

Powerful telescopes-- like this one on a mountaintop in Chile-- scan huge swaths of the sky.

With so many images and powerful computers to analyze them, the team has collected thousands of new supernovae, each one a snapshot of a different point in the universe's history.

♪ ♪ But there's another set of clues that might help paint a clearer picture of this mysterious dark energy.

(phone vibrating) And that's why Marcelle was so excited when signs of a gigantic cosmic explosion recently reached Earth.

This was something that we were all preparing for a long time.

WILLIAMS: 130 million light years away, two neutron stars had collided.

(explosion) The explosion was so powerful, it sent gravitational waves, ripples in the fabric of spacetime, across the universe.

SAURES-SANTOS: We received a signal from LIGO and Virgo.

(bell ringing) WILLIAMS: Like the ringing of a bell, the waves trigger sensors here on Earth at LIGO in the U.S., and Virgo in Italy.

Astronomers around the world point their telescopes towards the source of the signal, trying to find the light from the explosion.

SAURES-SANTOS: We're looking for the light corresponding to that "sound" that the gravitational wave detectors just heard.

WILLIAMS: And then they find it.

From Earth, a tiny dot that wasn't there before.

Several research teams around the globe spot this dot.

Oh... this was fantastic.

WILLIAMS: Fantastic because, for the first time, astronomers both "hear" and see a distant cosmic event.

(popping) That is the first ever... for any astronomer.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: That alone is remarkable.

But for the Dark Energy Survey, this type of event has opened a new window on the universe.

SAURES-SANTOS: With the gravitational wave data, we can do more.

The gravitational wave's signal contains information about the distance to the source that is independent from the light.

WILLIAMS: Gravitational waves provide a whole new source of information, helping to pinpoint the distance to these violent collisions.

And having two independent sources, both seeing and hearing an event, could reveal how fast the universe was stretching apart at the moment of the explosion.

(explosion) SAURES-SANTOS: Now we have a new way to attack the problem.

We can determine how fast the universe is expanding in between, and voila, we have information about dark energy.

WILLIAMS: For the team, combining gravitational signals with more tiny dots like this one might someday help reveal what dark energy actually is.

(camera clicking) SAURES-SANTOS: Everybody knew that we were, in some sense, witnessing the birth of a new field, a new area of research.

WILLIAMS: Astronomers may not have cracked the dark energy mystery, but the last 20 years have uncovered a new dramatic story: the ongoing epic struggle across the cosmos between dark energy and dark matter.

Astronomers are convinced that these are the two major players in the universe: dark matter, pulling the universe together, and dark energy, pushing the universe apart.

(rumbling) They're engaged in a cosmic tug of war that will determine nothing less than the fate of our universe.

They're really literally pulling in opposite directions.

So we know that dark matter and dark energy are in the grips of this cosmic competition, and which side, so to speak, has been winning has itself changed over time.

WILLIAMS: With each discovery, we're getting a clearer picture of how this battle has played out since the birth of the universe.

Just after the Big Bang, the universe was literally a hot mess, sizzling with radiation until dark matter and matter formed.

Dark matter and its gravity became the dominant driver in the universe, pulling together gas and dust, allowing galaxies and stars to form.

FISHER: And there was a time where normal and dark matter dominated the universe.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: In fact, for nearly nine billion years, dark matter's gravity was so strong it was slowing down the expansion of the universe.

But then, something changed.

About five billion years ago, the universe started accelerating in its expansion.

This moment-- when the universe stopped slowing down and suddenly started speeding up-- is known as the cosmic jerk.

FISHER: And really, starting just a few billion years ago, dark energy came to dominate the universe.

So, I would say we have evolved into a dark universe.

♪ ♪ WILLIAMS: Around the world, researchers continue the hunt, determined to find the secret ingredients that make the universe-- and everything in it-- possible.

FRANKLIN: You have people looking on all sides.

And somehow all of those things together are going to help us to understand.

It's kind of an incredibly great example of how science should really work.

That everybody should just follow their own curiosity and intuition.

And then together, it'll be brilliant.

♪ ♪ SAURES-SANTOS: It is a little bit humbling to look out there in the universe and say, "Most of it I don't understand."

But at the same time, of the part we do understand, we understand it so well that we were able to transform the world around us based on our knowledge.

And all of that success makes us confident that we will succeed here as well.

LYKKEN: We're just scratching the surface.

The whole history of science is finding out that the universe is bigger and more complicated, and more mysterious than anybody had thought.

We found out the earth was a planet, and then we had a solar system, and we have a galaxy, and we have billions and billions of galaxies.

And where's the end of that?

We don't know.

That is a big mystery.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ "NOVA Wonders" is available on DVD.

To order, visit shop.PBS.org, or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

"NOVA Wonders" is also available for download on iTunes.

♪ ♪

How Scientists Discovered Dark Matter

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S45 Ep106 | 2m 37s | What kind of clues led to the discovery of Dark Matter and its place in the universe? (2m 37s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S45 Ep106 | 1m 29s | Dark energy is spreading the universe apart—what’s it mean for astronomy in the future? (1m 29s)

Physics Is a Never-Ending Puzzle

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S45 Ep106 | 1m 8s | Physics rarely yields finite answers, but that doesn’t deter scientists. (1m 8s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S45 Ep106 | 5m 38s | Astrophysicist Priya Natarajan has loved atlases and maps since she was a little girl. (5m 38s)

What's the Universe Made Of? Preview

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S45 Ep106 | 28s | Peer into the universe’s deep unknowns to explore the mysteries of dark matter and energy. (28s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

National corporate funding for NOVA Wonders is provided by Draper. Major funding for NOVA Wonders is provided by National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the Alfred P....