Particles Unknown

Season 48 Episode 12 | 53m 28sVideo has Audio Description

Join the hunt for the universe’s most common—yet most elusive and baffling—particle.

Outnumbering atoms a billion to one, neutrinos are the universe’s most common yet most elusive and baffling particle. NOVA joins an international team of neutrino hunters whose discoveries may change our understanding of how the universe works.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Additional funding for this program is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Funding for NOVA is provided by the David H. Koch Fund for...

Particles Unknown

Season 48 Episode 12 | 53m 28sVideo has Audio Description

Outnumbering atoms a billion to one, neutrinos are the universe’s most common yet most elusive and baffling particle. NOVA joins an international team of neutrino hunters whose discoveries may change our understanding of how the universe works.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ NARRATOR: They're the most mysterious particles ever discovered, tiny ghosts hidden in our world.

Now scientists are on a mission to unlock their secrets.

They're called neutrinos.

The story of their discovery is almost impossible to believe.

DAVID KAISER: If they had bolted the detector in place, the nuclear bomb would've just smashed it to smithereens.

NARRATOR: With links to a dramatic Cold War defection.

FRANK CLOSE: He disappeared through the Iron Curtain, and for five years, disappeared off the face of the planet.

NARRATOR: And astonishing experiments that keep defying the laws of physics.

KERSTIN PEREZ: Even as someone who builds these experiments for a living, it just seems mind-blowing that they ever work.

NARRATOR: Today, scientists are using neutrinos to probe the edges of our detectable universe.

They're on a mission to reveal a hidden world of "Particles Unknown."

Right now, on "NOVA."

♪ NARRATOR: We live in a world of matter-- a realm of tiny particles far smaller than atoms that build the universe that we know.

But there is a mystery.

Scientists theorize there exists a hidden, parallel world of particles-- so-called dark matter.

So far, no one has managed to detect a single one.

But now there might be a way.

Of all the particles scientists have discovered, the most elusive, on the very edge of detectability, are neutrinos.

♪ KAISER: Neutrinos are really remarkable particles.

There are trillions and trillions of them streaming through our bodies, and we don't even notice.

They are kind of ghost-like, and yet they're everywhere.

NARRATOR: Everywhere and nowhere.

Neutrinos are so ghostly, they can pass through solid matter as if it didn't exist.

And yet they hold the secrets to why the stars shine and what our universe is made of.

RAY JAYAWARDHANA: The reason we care about these elusive particles is because they do play a fundamentally important role in the universe, in the nature of matter-- in some of the most violent cosmic phenomena.

NARRATOR: First theorized in the 1930s, they would soon become linked to nuclear secrets and a dramatic Cold War defection behind the Iron Curtain.

He goes off to Europe and never returns.

NARRATOR: Now the quest to detect neutrinos has triggered vast experiments all over the globe.

Even as someone who builds these experiments for a living, it just seems mind-blowing that they ever work.

NARRATOR: Today, scientists are on the cusp of an astonishing discovery.

Tantalizing evidence suggests neutrinos could be a doorway between our world of matter and the hidden world of dark matter, waiting to be discovered.

GEORGIA KARAGIORGI: It would be a game-changer.

What exactly are these particles?

What is its role in the evolution of our universe?

NARRATOR: The quest for answers has driven scientists to the edge of what is experimentally possible to reveal a universe we've never seen before.

♪ NARRATOR: Fermilab, in Batavia, Illinois.

World-renowned physics laboratory.

Thousands of scientists build enormous experiments to probe the very smallest particles that make up our universe.

(indistinct chatter) Leading one of the teams is Sam Zeller.

Hi, team.

My interest in physics started when I signed up for a field trip to come to Fermilab in high school.

It just blew my mind.

From that point on, I was a particle physicist.

♪ It turns out that the universe can be described by a small number of subatomic particles.

♪ NARRATOR: Today, scientists have discovered 17 basic particles that make up our universe.

♪ Some are the building blocks of atoms.

Others are the things that hold matter together.

It's an understanding of our world that physicists call the Standard Model.

PEREZ: The Standard Model of particle physics describes the most fundamental constituents of matter and how they interact with each other.

It is in fact the most mathematically well-defined physical theory we as humans have ever written down.

♪ NARRATOR: For 50 years, the Standard Model has withstood test after test, confirming the hierarchy of all the fundamental particles.

(device beeping) But one type remains far more mysterious than others.

They're called neutrinos.

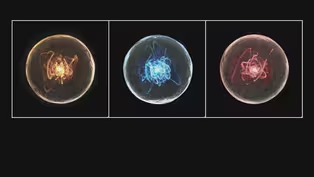

JAYAWARDHANA: A neutrino is a type of elementary particle, a basic fundamental building block of the universe, and they come in three different flavors.

KARAGIORGI: Neutrinos are everywhere.

They are produced in the sun.

There are neutrinos that were left over after the Big Bang.

Humans emit neutrinos.

CLOSE: Neutrinos have got no electric charge.

They've almost got no mass at all.

They're as near to nothing as you can imagine.

They're so reluctant to interact with stuff, they pass through the Earth as if it wasn't there.

NARRATOR: And yet, at Fermilab, scientists are constructing a complex two-stage experiment with the means to create them and study them.

♪ In its first stage, a powerful ring of magnets accelerates positively charged particles called protons to colossal speeds, sending them smashing into a target.

The collision creates a shower of new particles, including a powerful beam of neutrinos.

150 trillion per second pass through the Earth at nearly the speed of light, racing towards the second stage-- three giant neutrino detectors.

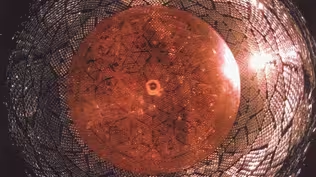

The largest is called ICARUS.

Once complete, this immense tank filled with a web of electronics and cryogenic liquid will be bombarded by hundreds of trillions of neutrinos, all in the hope of catching just one each minute.

♪ That alone will be a remarkable achievement.

(device beeping) But the scientists have even bigger ambitions.

ZELLER: One of the big goals here at Fermilab is to try to search for possibly a new type of neutrino that no one has yet observed.

NARRATOR: Experiments have hinted there could be an even more elusive neutrino beyond the three types already known to exist.

Some have suggested that it could be a link to a hidden realm of particles that could finally lead to new discoveries beyond the Standard Model.

ZELLER: If we found evidence for a new type of neutrino, that would be really astounding.

That's what gets me excited in the morning.

That's what gets me coming in to work.

It would be a major and massive discovery.

NARRATOR: Making that discovery would be groundbreaking.

Because while ordinary neutrinos are extremely hard to detect, this fourth type of neutrino could break the Standard Model.

What brought them to this moment-- and possibly to the brink of upending one of the bedrocks of modern physics?

♪ That story begins almost 100 years ago half a world away.

In Rome.

Physicist and historian Professor David Kaiser has traveled here, to the place where, in the 1930s, scientists were investigating the inner workings of the atom.

KAISER: For millennia, for thousands of years, people had come to believe that the world was made of atoms, and those atoms were the smallest thing there was.

In fact, the word atom even means "unbreakable" or "indivisible"-- the smallest piece.

♪ NARRATOR: But by the early 1900s, scientists had revealed a deeper hidden structure.

KAISER: If you think about an atom, it's about a nanometer, about a billion times smaller than a meter, roughly.

The inside, the deep core of an atom, the nucleus, is about 100,000 times smaller than that.

So we're really zooming in powers of ten, powers of ten, getting to unimaginably tiny scales.

NARRATOR: During the early 20th century, scientists discovered the atom's tiny nucleus contained protons, particles with a positive electric charge.

These protons held in place a cloud of negatively charged electrons that formed the atom's outer limit.

It seemed that protons and electrons were the only two components of all atoms-- permanent and fixed.

But scientists had also found something shocking: some types of atoms seemed to break apart.

KAISER: That was just jaw-dropping.

Literally, it contradicts the name of the thing itself.

Atoms are supposed to not break down.

♪ NARRATOR: It was as though certain atoms had too much energy.

The nucleus would spontaneously transform and spit out an electron.

This phenomenon was a type of radioactivity known as beta decay.

JAYAWARDHANA: It appeared to be this sort of mysterious energy leaking from or emanating from certain atoms.

NARRATOR: This process was remarkable in itself, but when scientists measured the energy of the electrons from beta decay, something was wrong.

KARAGIORGI: One of the basic principles in all sciences is that energy can change from one form to the other, but the total sum must be conserved.

♪ NARRATOR: This is the principle of conservation of energy.

From collisions in the macro world to the behavior of tiny particles, the principle states that energy should never disappear.

But when scientists measured the energy of the electrons from beta decay, that's exactly what seemed to happen.

KARAGIORGI: So every time, rather than having energy conserved, what they were seeing is that some amount of energy would be missing.

NARRATOR: Where was the energy going?

It seemed that the particles themselves were breaking the fundamental rules of physics.

♪ In 1926, a young Italian physicist called Enrico Fermi was working at the University of Rome's Physics Institute.

It was here that Fermi probed into the developing field of nuclear physics.

KAISER: Enrico Fermi was really a towering figure of 20th-century physics-- by any measure, one of the greatest physicists of the 20th century.

This is the site where Fermi built what became an absolutely world-class group of researchers.

NARRATOR: They were known as the Via Panisperna Boys.

KAISER: This is really an iconic photograph.

It captures them in the middle of what would become world-changing research.

Fermi himself was remarkably young-- he was just 26 years old, and already he'd been made the big senior professor around which this young group would come together.

They referred to Fermi as the Pope, he was the great leader.

Rasetti was next in line, he was a cardinal.

The person taking the photograph, the very young Bruno Pontecorvo, the youngest member of the group, they called him the Puppy.

NARRATOR: The group's ideas would have a profound impact on the world.

♪ In October 1931, they invited a group of the world's leading physicists to a conference held at the Physics Institute.

High on the agenda was the problem of the missing radioactive energy.

One scientist at the conference, the famous Wolfgang Pauli, proposed a radical idea.

KAISER: Wolfgang Pauli had written a letter to colleagues.

And he put forward what he called a desperate remedy, a "versweifelten Ausweg"-- it was just ridiculous.

And he says so in his letter.

It's a really quite strange-sounding idea.

What if there was a new type of particle in the world that no one had ever seen or detected before?

♪ NARRATOR: Pauli suggested that instead of just an electron, perhaps there was an unknown particle that was carrying away the missing energy.

KAISER: Very few people seem to have been convinced that this was the right way to go.

At that time, physicists were quite confident there existed two basic kinds of particles, electrons and protons.

But Pauli was suggesting, "Let's make this enormous leap."

NARRATOR: A new particle of matter seemed a step too far.

♪ But for Enrico Fermi, the Pope of Via Panisperna, he took the wacky idea and ran with it.

Fermi dedicated the next two years of his life to describe the obscure ghost particle.

It would be neutral, and carry no electric charge.

It would be tiny, far smaller than an electron.

And it would pass through atoms as if they weren't there at all.

He named the particle the neutrino, Italian for "little neutral one."

KAISER: This was a really quite remarkable step.

But many physicists, Fermi included, thought that it should be nearly impossible-- perhaps impossible forever-- to detect such a particle even if it really exists.

♪ NARRATOR: Outside the intellectual fervor of the lab, fascism was about to cast a shadow over the neutrino mystery.

In 1939, Fermi immigrated to the U.S.A. and was quickly put to work.

He helped to develop the first operational nuclear reactor that led eventually to the atomic bomb.

But not everybody had forgotten about the elusive neutrino.

♪ Bruno Pontecorvo, the Puppy of the Via Panisperna Boys.

Upon moving to England after the Second World War, he continued to think about neutrinos until his life took a shocking turn.

CLOSE: Pontecorvo was a man who created big ideas.

The work that he did on neutrinos alone could have won him certainly one Nobel Prize, and been a candidate maybe for two.

NARRATOR: But it wasn't to be.

In 1950, in the midst of the Cold War, Pontecorvo and his family mysteriously went missing.

Bruno Pontecorvo disappeared through the Iron Curtain in 1950, and for five years, disappeared off the face of the planet.

NARRATOR: Only after five years of silence did he reappear in the Soviet Union.

♪ So, what happened?

Was he kidnapped?

Was he a spy?

Professor Frank Close has spent years researching Pontecorvo and his mysterious disappearance.

He has come to the British National Archives in London.

Earlier in his life, Pontecorvo had been a member of a communist party.

And there are now British intelligence files under his name.

CLOSE: Looking at these old folders, they're worn down the sides.

They have red stamps, "top secret."

The case of Pontecorvo.

It is dripping with intrigue.

(chuckles) ♪ NARRATOR: After the war, while working for the U.K.'s atomic energy program, Pontecorvo devised a method to try and detect neutrinos.

He reasoned that nuclear reactors-- which derive energy from splitting atoms-- should produce neutrinos in vast quantities.

But the government classified his paper.

Now, I conjecture that this paper was classified secret because, if you could indeed detect neutrinos coming from a nuclear reactor, you would be able to work out how powerful the nuclear reactor was.

So they classified it.

♪ NARRATOR: As the Cold War escalated, the U.S.A. became paranoid of atomic espionage.

In 1950, the Rosenberg spy ring was uncovered.

And it triggered a communist witch hunt.

A secret letter reveals the FBI wrote to a British intelligence service about Pontecorvo.

CLOSE: "The FBI now ask if we can send them any information "which would indicate that Pontecorvo may be engaged in communist activities."

The letter was received in London on the 19th of July.

Five days later, Pontecorvo goes off to Europe and never returns.

♪ NARRATOR: Flight manifests reveal Pontecorvo and his family flew from Rome, across Europe, to Helsinki, alongside two suspected KGB agents.

Pontecorvo's son, just 12 years old at the time, revealed they were then driven across the border to Moscow-- with Bruno in the trunk.

CLOSE: He said to me, "I knew something was up."

(chuckles) NARRATOR: Frank believes a Soviet mole passed the FBI letter to Moscow, who then pressured Pontecorvo to defect.

There's no clear evidence that he had been a spy, but whatever his reason for leaving, Bruno's time in the West was over.

CLOSE: Was he a spy or not?

We don't yet know.

In any event, it was clear that Pontecorvo was a top-quality scientist who had taken his brain to the Soviet Union.

NARRATOR: By 1950, the U.S.A. and the Soviet Union were engaged in a nuclear arms race.

With it came a new opportunity to hunt for neutrinos.

KARAGIORGI: When a nuclear bomb goes off, there is this huge cascade of particles that spews out: protons, electrons, a lot of light particles carrying off energy.

And along with these particles spewing out, lots and lots of neutrinos come out for free.

NARRATOR: If neutrinos were real, could a nuclear weapon finally be the key to detect them?

In 1951, a young American called Fred Reines was working on the U.S. nuclear program at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

It was here that Reines, along with his colleague Clyde Cowan, decided to take advantage of destructive bomb tests to investigate the mystery of the missing neutrino.

KAISER: Reines went back to a question that had been kind of abandoned in the decades before the Second World War, the question of, could physicists ever actually detect these very strange, elusive, ghost-like particles?

NARRATOR: They called their mission Project Poltergeist.

For detecting the neutrino, the good news was, you could calculate the chance of doing it.

And the bad news was, it was almost zero.

NARRATOR: Reines and Cowan needed to tip the odds in their favor, and knew a nuclear bomb test could be the key.

An atom bomb should produce thousands of times more neutrinos than even the biggest nuclear reactor.

But it also created a problem.

If they had bolted the detector in place, the nuclear bomb would've just smashed it to smithereens.

So instead, the proposal was to dig a shaft about 150 feet deep right near where the bomb would eventually be detonated above ground.

NARRATOR: The team planned to drop a detector down the shaft to avoid the shockwave of the bomb.

KAISER: Inside that shaft, they would pad the bottom with foam and feathers and kind of, like, mattress cushions.

It was, I mean... (chuckles) ...a creative, ambitious, and maybe slightly crazy kind of idea to try to catch these neutrinos in the midst of this very dramatic, very worldly set of events in the early years of the Cold War.

♪ NARRATOR: Work digging the shaft had begun, but the head of physics at Los Alamos was concerned that the experiment couldn't be repeated.

He urged the team to find another way.

Couldn't they use a nuclear reactor instead?

Late one evening, Reines and Cowan had a realization.

In the same way that the nucleus of an atom could decay and release a neutrino, they knew in theory the process should be reversible.

On the rare occasion a neutrino could interact with a nucleus, it should produce two new particles, called a neutron and a positron.

And if they traveled through the right medium, those two telltale particles should produce two distinctive flashes of light.

KARAGIORGI: So Reines and Cowan built a detector, essentially a big tank filled with a solvent that could pick up this two coincident signal blip deep under a nuclear reactor.

♪ NARRATOR: After five years of experiments, in 1956, finally, they got their answer.

♪ They recorded the two telltale flashes of light.

♪ For the first time, they saw evidence of the elusive neutrino.

What they had done was a remarkable achievement, one that seemed impossible.

♪ KAISER: Neutrinos exist.

They're real and they're part of the world.

They're not only a clever idea.

Knowing neutrinos exist put a whole extra set of investigations on a kind of firmer path.

♪ NARRATOR: If neutrinos were pouring from nuclear reactors on Earth, then surely they would be generated in abundance in the largest nuclear furnaces of all.

Stars.

KAISER: For a long, long time, scientists have been wondering, what makes the stars shine?

What drives that enormous output of energy?

♪ KARAGIORGI: People theorized that our sun is like a giant nuclear reactor, except, rather than heavier elements breaking down into smaller ones and releasing energy, you have lighter elements that fuse together through nuclear fusion.

♪ NARRATOR: In the heart of the sun, tremendous heat and pressure force hydrogen nuclei to fuse together to make helium.

And, in theory, vast quantities of neutrinos that pass freely through the sun and out into space.

So if we could detect neutrinos from the sun, we could learn about the processes that fuel it.

We could peek inside the core of our sun.

NARRATOR: In the historic gold mining town of Lead, people descend into the depths of the Earth.

(indistinct chatter) NARRATOR: But no longer to mine precious metal.

They're hunting for neutrinos.

It was here in 1965 that an experimentalist called Ray Davis came to try and prove what makes the sun shine.

KAISER: Ray Davis got very excited that there is this new thing in the world called a neutrino.

He began realizing that other kinds of nuclear reactors that occur throughout the universe, like stars, they should be spewing out these neutrinos all the time.

NARRATOR: But catching them wouldn't be easy.

Calculations showed that neutrinos from the sun would be so faint, a detector near the Earth's surface would be overwhelmed by background radiation.

His only option was to go to the bottom of a mine.

Beneath almost a mile of solid rock, Davis's team built a steel tank the size of a house and filled it with 100,000 gallons of dry-cleaning fluid.

In theory, if a neutrino from the sun collided with a chlorine atom inside the tank, it would cause a reaction that Ray Davis could detect.

CLOSE: Here was something that was completely fresh.

Nobody knew anything about it.

But the key thing was that if neutrinos hit chlorine, which you could get in cleaning fluid, it would turn the atoms of chlorine into a radioactive form of argon.

And that's when Davis got excited, because he was a radiochemist, and for him, detecting radioactive forms of argon was easy street.

NARRATOR: Scientists had calculated that around a million trillion neutrinos from the sun should pass through Davis's tank each minute.

But the probability of them hitting the fluid and making an argon atom was so small, Ray Davis could only expect to find ten individual atoms of argon from ten neutrino collisions per week.

JAYAWARDHANA: His task was almost impossible.

Many of his own physicist colleagues doubted this experiment would ever work.

♪ CLOSE: He was having to convince people that out of these millions and millions and millions and millions of atoms inside this tank, he could identify the collisions of one or two and convince you that these were neutrinos coming from the sun.

NARRATOR: Around each month, Davis flushed out the giant tank to extract the argon atoms.

To everybody's amazement, he found them.

(machine whirring) But there was a problem.

Instead of detecting the number of atoms that theory predicted, his measurements fell short.

KAISER: They knew the target number based on the nuclear physics theoretical explanation of how stars shine, and that led to a very particular target number.

And Davis's remarkable experiment kept coming in not close to it, not 80 percent, but only at one-third of that target number.

NARRATOR: What happened?

Had the experiment gone wrong?

Another scientist carried out a blind trial to test the accuracy of Ray's atom detection.

KAISER: A colleague put in 500 kind of rogue atoms without telling Davis the number.

And Davis was able to go through the whole process, sift it through, and he counted exactly the number that had been put in.

NARRATOR: If the experimental results were accurate, then perhaps scientists had gotten their theory about neutrinos from the sun wrong.

CLOSE: Everybody was blaming everybody else.

There were even suggestions, has the sun already burnt out in the core?

It was just an enormous puzzle.

All these advances in understanding how stars shine, and then hitting this kind of brick wall where theory and experiment just would not agree with each other.

NARRATOR: The puzzle became known as the solar neutrino problem.

♪ 1970, 20 years since Bruno Pontecorvo defected to the Soviet Union.

♪ Even after all that time, his life behind the Iron Curtain remained shrouded in secrecy.

But in a government lab outside Moscow, Pontecorvo worked tirelessly to explain the puzzling behavior of neutrinos.

He suggested that instead of just one, there may be two or even three different kinds of neutrino-- known as different flavors.

♪ If this wasn't strange enough, he calculated that something peculiar might happen as they traveled through space.

A neutrino would always be born as one definite flavor, but over time, it would change its identity.

It would transform, mixing back and forth between the three different types.

This was called neutrino oscillation.

♪ Pontecorvo's idea really is, it's, it's sort of delicious.

These neutrinos could be not taking one identity, dropping that, adopting another one, dropping that, but going into this even stranger mixture, where they're in neither and both states at once.

NARRATOR: It was a bold idea.

No other fundamental particle seemed to spontaneously change its identity.

But if neutrinos were transforming into flavors that Ray Davis's detector couldn't see, it might explain why two-thirds of the neutrinos from the sun appeared to be missing.

But there was a catch.

The Standard Model, the most precise scientific theory in human history, made one important prediction that stood in the way.

PEREZ: The Standard Model anticipated neutrinos would be completely massless.

They would have no mass at all, much like the photon of light.

And if they had no mass, that meant that they could not oscillate.

NARRATOR: If neutrinos had no mass, one of Albert Einstein's most important theories predicted that neutrinos could not possibly oscillate.

KAISER: There is this mind-boggling phenomenon from Einstein's relativity that says that a clock that is moving closer and closer to the speed of light will tick at a slower and slower rate.

If that clock were moving literally at the speed of light, it would never tick at all.

No time would pass for that object that moves at exactly the speed of light.

NARRATOR: According to Einstein's theories, the faster a particle travels, the more its internal clock slows down.

A particle with no mass can only travel at the speed of light, which is where time stops.

So if a neutrino had zero mass, it would not experience the passage of time, and would never be able to change.

If a particle has zero mass, what that means is that its internal clock is not ticking.

There's no way for that particle to experience time.

If there's no passage of time, then how could they change over time from one identity to another?

NARRATOR: If neutrino oscillation was real, neutrinos must have some mass.

But could the Standard Model really be wrong?

♪ Throughout the 1950s and '60s, clues from experiments performed at CERN, alongside Fermilab, helped to lay the foundation of the Standard Model.

What they found revolutionized our understanding of the particles that make up our universe.

FILM NARRATOR: By means of this machine, it is possible to see the tracks of sub-nuclear particles, the smallest particles known to man: the electron, the positron, the photon, and the neutrino... NARRATOR: Over the years, work at CERN led to groundbreaking new technologies: medical advances like PET scans; even the birth of the World Wide Web.

Perhaps CERN's biggest success came in 2012.

Nearly 50 years after the Standard Model was proposed, physicists detected the final particle it predicted-- the Higgs boson.

I think we have it.

(cheers and applause) NARRATOR: Finally, all the pieces needed to describe the detectable physical universe seemed to be in place.

Along with the Higgs boson, there are force carriers, like the photon of light.

Quarks, which form the nuclei of atoms.

Leptons, including the electron, muon, and tau.

And three corresponding flavors of neutrinos.

KAISER: It is a map of what's out there, what we're made of, and how we fit-- all of us.

We are made of these things.

And that is a kind of basic understanding of nature, of our own world, that I, I think is, is just a remarkable human achievement.

NARRATOR: And yet, for all its success, the Standard Model had no equations to explain how or why the neutrinos would have mass.

For Ray Davis and his missing solar neutrinos, it seemed an unsolvable paradox.

For decades, Davis persists, but he still only finds one-third of the neutrinos that were supposed to be coming from the sun.

Well, we've been carrying on this experiment for about 20 years right here.

But we're still observing a low flux of neutrinos.

NARRATOR: Eventually, the problem is too big to ignore.

In the 1990s, scientists in Canada and Japan construct a new generation of supersized neutrino detectors to finally settle the mystery.

(explosion roars) One of them lies deep beneath Japan's Ikeno Mountain.

Scientists fit 11,000 light detectors to the inside of a gigantic container and fill it with 50,000 tons of ultra-pure water.

This $100 million detector is named Super-K.

The Super-K experiment ended up being a game-changer.

NARRATOR: In the rare event that a neutrino collides with the liquid in Super-K, the reaction produces a trail of light which the sensors can pick up.

Unlike Davis's detector, this signal allows scientists to calculate which type of neutrino has hit and the direction it came from.

Super-K allows scientists to test the theory of neutrino oscillation by catching them from a new source: the Earth's atmosphere.

♪ Theory suggests that when radiation from space hits the atmosphere, it creates neutrinos that travel directly through the Earth.

Some travel a short distance, but others will come from the other side of the planet to reach the detector.

If the neutrinos are not changing, the combination of flavors they record coming from a short distance will be the same as those coming from afar.

If they are changing over a long distance, the combination of flavors will be different.

After two years of recording data, the team finally has an answer.

KARAGIORGI: What they were seeing was that one type of neutrinos was depleting when traveling through the Earth.

The Super-K results combined with results from another experiment were able to definitively show that neutrinos can change from one type to the other.

For that to happen, you must have non-zero neutrino mass.

NARRATOR: The results are groundbreaking.

Neutrinos change their identity.

Neutrinos have mass after all.

And the Standard Model's prediction of the nature of neutrinos must be wrong.

KAISER: With the new input, the evidence that neutrinos really oscillate, they really change their identities, therefore they really, really have a mass, this long-standing, decades-long challenge to understand the solar neutrino problem finally fell into place.

NARRATOR: Nuclear fusion in the sun produces one type of neutrino.

But on the long journey through space, the neutrinos oscillate, and turn into a mixture of all three.

On Earth, Ray Davis's detector only picked out one flavor.

His results had been accurate all along.

37 years after the experiment began, Ray Davis was awarded the Nobel Prize.

(cheers and applause) For Bruno Pontecorvo and his theory of oscillations, sadly, the discovery came too late.

CLOSE: Nobel Prizes aren't everything, but by the time the oscillations had been sorted out and the whole thing finally understood, Pontecorvo was dead.

So that's the final tragedy of his life.

NARRATOR: After almost 100 years of research and discovery, today, neutrino physicists face perhaps their biggest puzzle yet.

The Standard Model's equations, which are so precise for other particles, cannot explain why neutrinos have mass or why they oscillate.

It's a sign that our understanding of matter is still incomplete.

♪ Today, neutrino experiments are in overdrive, hunting for clues.

KAISER: We're in the midst of, really, a neutrino bonanza-- I mean, they're just, they're popping up all over the field of physics.

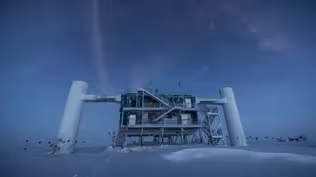

♪ NARRATOR: At the South Pole, scientists have built the largest neutrino detector on the planet.

It's made of more than 5,000 sensors drilled into a cubic kilometer of Antarctic ice.

It's known as IceCube.

♪ KAEL HANSON: IceCube is in this, this huge field around me-- I'm sitting, kind of standing in the middle of IceCube.

It's kind of amazing to think that we were able to haul something like five million pounds of cargo down to the South Pole-- this is instrumentation, cables, drill equipment, fuel... NARRATOR: As well as probing neutrino oscillations, IceCube acts like a neutrino telescope, catching cosmic neutrinos from billions of light years away.

This is the universe that has really only been opened to our eyes for the last 50 years.

♪ There's all kinds of discoveries that are waiting out there.

NARRATOR: With new experiments like IceCube, scientists believe that neutrinos may reveal discoveries beyond the Standard Model.

Neutrinos could even help unlock one of the biggest mysteries in physics today.

♪ It seems that most of what our universe is made of is missing.

PEREZ: The whole quest of particle physics is to explain the matter contents of the universe.

And we seem to be doing this phenomenally good job.

You crank through the math of the Standard Model, and everything makes sense.

And yet it only describes some very small fraction of what the universe is made out of.

NARRATOR: Looking into space, cosmologists can see the gravitational influence of a material that binds entire galaxies together, but that is completely invisible to their detectors.

Scientists call this material dark matter, because nothing in the Standard Model can describe what it is.

And yet, it seems to be what most of the matter in the universe is made of.

CLOSE: The Standard Model is very good at describing about five percent of the universe.

95% of the stuff is an utter, complete mystery, made of dark stuff, whether it's dark matter or dark energy.

And what either of those are, we don't know.

All we really know about dark matter is that it creates gravity, but it's not interacting with the instruments that we have used to observe the universe.

KAISER: Whatever is filling space, much more of it than the ordinary matter that makes up us and our planet and our stars, it's some other, other kind of particle.

NARRATOR: Whatever dark matter particles are, scientists must look beyond the Standard Model to find them.

Neutrinos might be the key.

♪ At Fermilab, for over 20 years, scientists have been investigating neutrino oscillations.

What they've found doesn't add up.

ZELLER: The first observation that something was amiss was in the late 1990s.

Something we don't quite understand is going on.

♪ NARRATOR: At Fermilab, scientists fired a beam of neutrinos just 500 yards to their detector.

Neutrinos oscillate too slowly for the detector to see them change over such a short distance-- at least according to theory.

But the detectors saw an increase in one type of neutrinos.

Neutrinos seem to oscillate faster than is theoretically possible.

KARAGIORGI: The strange thing that we're seeing is that neutrinos seem to be changing from one type to the other much faster than expected.

In order for that to happen, we think it's possible that there are extra neutrinos out there.

NARRATOR: In addition to the three flavors of neutrino that the Standard Model describes, there could be a fourth neutrino that affects them, making them oscillate faster.

Scientists call it a sterile neutrino, and it's never been directly detected.

PEREZ: So we call it a sterile neutrino, in essence, just because it interacts even less with other particles than the regular neutrinos do.

♪ NARRATOR: A sterile neutrino would be the ultimate ghost particle.

It would never collide with atoms in our world.

No detector could ever see it.

But it may reveal itself through its effects on the neutrinos we can see.

KARAGIORGI: The only way that we can tell they exist is through their effects on neutrino oscillation.

NARRATOR: If sterile neutrinos exist, it would break the neat symmetry of the Standard Model that organizes particles in groups of three.

What if there's a fourth kind of neutrino, a so-called sterile neutrino?

Well, where would you put that on our map?

There's no room to kind of shoehorn in, to squeeze in a fourth neutrino.

So I think there really is a lot riding on this.

NARRATOR: If they're real, sterile neutrinos would have mass, but not interact with our detectors-- just like dark matter.

They could be the first particle of dark matter ever discovered, and through their effects on the neutrinos we can see, they could give scientists a window into another world.

KAISER: The neutrino might be a kind of link, almost a kind of messenger or portal to this whole other possible kind of stuff out there.

NARRATOR: At Fermilab, scientists are edging towards the truth.

ZELLER: I think we're getting a lot closer.

Neutrino physicists are incredibly patient.

It takes a long time for us to collect our data, and we really want to be sure in what we're seeing before we potentially make a very important discovery.

We're trying to answer some of the biggest questions in physics.

I think it's really unique that neutrinos may hold all the answers.

NARRATOR: What began as a hypothetical particle that no one thought possible to detect could now be a key that unlocks what most of our universe is made of and how it works.

KAISER: Every time we look up, there seem to be these very curious neutrinos.

They are constantly bedeviling our mental maps of how we carve up nature and try to dig in and study it.

And that's just amazingly exciting.

So they've gone from, "Maybe they exist, maybe they don't, we might never know," to being our surest ticket to the next step.

KARAGIORGI: History has shown that with every little bit of progress, we've learned huge, surprising things about our cosmos.

To me, that's really exciting.

And I'm curious to know, where else could we go?

NARRATOR: Wherever we go, neutrinos could be our guide.

♪ ♪ ALOK PATEL: Discover the science behind the news with the "NOVA Now" podcast.

Listen at pbs.org/novanowpodcast or wherever you find your favorite podcasts.

ANNOUNCER: To order this program on DVD, visit ShopPBS or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

Episodes of "NOVA" are available with Passport.

"NOVA" is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

♪ ♪

This Detector Can Catch Cosmic Neutrinos

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S48 Ep12 | 3m 20s | Neutrinos could help unlock one of the biggest mysteries in physics today. (3m 20s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S48 Ep12 | 30s | Join the hunt for the universe’s most common—yet most elusive and baffling—particle. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

Additional funding for this program is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Funding for NOVA is provided by the David H. Koch Fund for...