The Cost of Inheritance

Season 12 Episode 1 | 55m 23sVideo has Closed Captions

Exploring reparations to illuminate the scope and rationale of this complex debate.

THE COST OF INHERITANCE, an America ReFramed special, explores the complex issue of reparations in the U.S. using a thoughtful approach to history, historical injustices, systemic inequities, and critical dialogue on racial conciliation. Through personal narratives, community inquiries, and scholarly insights, it aims to inspire understanding of the scope and rationale of the reparations debate.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for America ReFramed provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Wyncote Foundation and Reva and David Logan Foundation. Funding for The Cost...

The Cost of Inheritance

Season 12 Episode 1 | 55m 23sVideo has Closed Captions

THE COST OF INHERITANCE, an America ReFramed special, explores the complex issue of reparations in the U.S. using a thoughtful approach to history, historical injustices, systemic inequities, and critical dialogue on racial conciliation. Through personal narratives, community inquiries, and scholarly insights, it aims to inspire understanding of the scope and rationale of the reparations debate.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch America ReFramed

America ReFramed is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ (woman vocalizing) LOTTE LIEB DULA: My mother had died.

I was opening up a whole bunch of boxes.

Each box was like a time capsule.

I found a little black book, and I started paging through and I realized this is a plantation, and here is a list of enslaved people.

They're listed by name, age, and value.

♪ ♪ Cornelius, age eight, $500.

John, age 20, $1,100.

(fading): Jack, 15... SARAH EISNER: I have known that my ancestors were enslavers since as long as I can remember.

What really struck me was seeing names.

DULA: Tom, 13, $700.

July, age ten, $600.

TA-NEHISI COATES: We recognize our lineage as a generational trust... DULA: Jake, age ten, $600.

COATES: ...as inheritance.

And the real dilemma posed by reparations is just that: a dilemma of inheritance.

DULA: Joe P., 24, $1,200.

James... MARY FRANCES BERRY: By 1900, there was something like a million Black people who had actually been slaves who were still around.

If the government had given reparations to those small number of people, perhaps the question would not have come back to bite them later on that nothing had been done.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.: Now, when we come to Washington, we are coming to get our check.

CHERYLLYN BRANCHE-BAKER: We speak the names of those who came before us: Verana.

ALL: Ase.

BRANCHE-BAKER: Barts.

ALL: Ase.

BRANCHE-BAKER: Blacklock.

ALL: Ase.

BRANCHE-BAKER: Blair.

ALL: Ase.

COATES: The matter of reparations is one of making amends.

I can't breathe.

COATES: But it is also a question of citizenship.

MAN: Say her name!

EISNER: Seeing those names, it humanized it for me.

Why didn't somebody do something more to stop this within the family?

There are 44 souls listed in this ledger.

If our family enslaved others, then I've got some repair work I've got to do.

♪ ♪ WOMAN: Ase.

Ase.

Ase.

(woman vocalizing) Good morning, everybody.

Underground Tours?

- Yeah!

PATT GUNN: Well, you know, we Gullah Geechee people, we don't say good morning, what we usually say is, "How y'all be?"

CROWD: We be fine.

Well, thank you so very much.

And I am Gullah Geechee, Roz is Gullah Geechee.

Gullah Geechee people are direct descendants from those enslaved West Africans that came here during the transatlantic slave trade.

On this tour, we're gonna take you on a journey from slavery to freedom.

I'm gonna do truth-telling, I'm gonna do reconciliation, I'm gonna do healing, and I'm gonna push for repair, which means I'm going to push for reparations.

Can I get an amen?

CROWD: Amen.

♪ ♪ (seabirds squawking) This is where the story really starts for me.

I was born and raised in California, but I would come every summer to Savannah in the Hilton Head area to visit my grandparents, and we would visit the family cemetery.

(insects buzzing) And that's where my knowledge of family history started, just walking in that cemetery and being told the truth about history.

My family first came here around 1770.

The first people that my family enslaved came to them through marriage.

My family had owned thousands of acres, and then between, uh, 20 and 40 humans that were enslaved.

Seeing the names of those that particularly George Adam Keller had enslaved, because he is the father of all these children that then became, you know, me-- it humanized it for me.

I really wanted to do more research into who were these enslaved people and did they have descendants in the area?

♪ ♪ When I came here as a little girl, this corner of the cemetery wasn't quite as overgrown as it is today.

In the corner, there's a tiny little headstone.

I remember asking, you know, "Who's Rachel Butler?"

(voiceover): Rachel Butler was favored and she was treated special and she was so well-loved by the family.

She was buried here, away from her own family.

You can't both love someone and enslave them.

That always really struck me.

I feel, I feel like this is probably the first place in my life that I felt shame.

I have always been seeking for her descendants, and in that seeking is sort of how I found Randy and the Quarterman family.

(drum playing) (woman singing indistinctly) ♪ Was a day of rejoicing... ♪ (continues indistinctly) (rhythmic clapping) (congregation singing along) RANDY QUARTERMAN: My family has been in this area since the mid-1800s.

But my family history, whether it was slavery or Jim Crow, was not passed down because of the pain that they had to relive.

I understand their way of surviving, but it stripped us of some of our identity.

I was born in Okinawa, Japan, in 1975, my father was drafted into the Air Force for Vietnam.

I stayed in Japan and then I came back here when I was 13.

My father would just tell me I'm a man without a country.

♪ ♪ ROY QUARTERMAN: It was hard to look at the United States in-- as my country when I wasn't treated equally.

During the Jim Crow law, we lived in a segregated area, a segregated high school.

I'd been shot at by whites just for being Black.

Okay?

I had to run for my life many times.

Okay, so... ♪ ♪ RANDY: On this road where we at now, Meinhardt Road, the right side, that's where the all the Black families lived.

To the left side of the street, that's where all the whites lived.

And my grandmother always told me, "Hey, when you go play, don't go down the left side of the road."

To learn, at that point, of being inferior to somebody else, that built anger in me.

EISNER: In 2019, I was speaking with my cousin Bill, who lives in the Savannah area.

Bill said, "The Quarterman family still own "this plot of ten acres of land that George Adam Keller gave, uh, Zeike Quarterman in the 1800s."

ROY: When we found out the land was given to Zeike, he came alive again, to us.

PASTOR: If you got anything on your heart right now, this is the time, hallelujah... RANDY (voiceover): In August 2019, I had an email from Sarah acknowledging who her family was, and if I was a descendant of Zeike Quarterman, who was enslaved by, uh, George Adam Keller.

♪ ♪ I was just, like, taken offtrack a little bit.

EISNER: I was definitely nervous and scared.

RANDY: My question was, "What are they doing here?

What, what's the... what's going on?"

EISNER: I remember thinking, "What have I done?

What if they yell at me?"

If they do, they do.

They, they have every right to be angry.

RANDY: I consulted with Patt Gunn, somebody that was doing this type of work and understanding it.

GUNN: And so, you're standing in a sacred ground.

This is a slave-holding bin, we believe.

RANDY: She told me, said, "Hey," you know, "your ancestors is on your back.

"It, it's a special moment for you.

You need to engage."

♪ ♪ (birds chirping) It's right here.

See, the one, two... EISNER: Yeah.

...three, four.

And this is, is... is staggered into a corner is, like, where our house would be right here.

♪ ♪ (voiceover): For me and my family, we, we know this as heirs property, land that's passed down through family generations, that has no will to say, "This person owns the land."

It should have been Zeike's house.

This probably was the house structure that was... they lived at.

(voiceover): But the land is not in our possession.

A court-appointed lawyer became the executor of our property.

See, it's like old bricks from back then.

(voiceover): And then, Sarah was like, "Hey, I really want to get you some help to try to clear this title."

EISNER: I thought, "This is so obviously a case of reparations, because of America's first attempt at reparations right in that area.

♪ ♪ (gunfire) GUNN: The emancipation of slaves on the Georgia coast happened on the 21st of December 1864.

On a cold winter's morning, they trekked from Atlanta all the way down to Savannah, and General William Tecumseh Sherman was the Union general contracted by President Lincoln.

He said, "I'm gonna burn everything down until I get to the sea."

(horse neighs) (gunfire) (pig squealing) GUNN: And when he got to Savannah, the mayor of the city stood at city hall with a white surrender flag, so Sherman came in and freed the slaves.

♪ ♪ 20 preachers met with Sherman and his soldiers.

The conversation was, "What does freedom mean to you?"

They had one spokesperson, Reverend Garrison Frazier, and he said, "Freedom, to us, means land."

They wrote up Field Article Number 15 for the Georgia and South Carolina Sea Islands.

40 acres, a mule, and $200 for seed.

They began to plant their land and everything was fine.

One year later, Abraham Lincoln is assassinated on April 15, 1865, they rescind the law and they took the land back.

They gave the planters $20,000 checks.

The enslaved got nothing.

RON DANIELS: Reparations has been here and have been worked on for generations.

From the very beginning, people were knocking on the door saying, "We are owed for our labor."

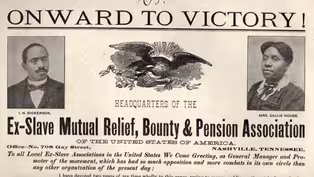

BERRY: Callie House, she was born a slave.

She went out all around in the community telling Black people that they ought to ask the government to get some money, because, many, they were poor and they were desperate.

By 1900, she had 300,000 dues-paying members.

It was the largest organization of Black folk that had existed.

Pretty soon, her activities came to the attention of the government, and they convicted her of fraud.

The federal charge was that, "At a time "when you should have known that the federal government "would have never give Negroes anything, "why were you telling Negroes they should organize to try to get something?"

(chuckles) They sent her to prison to serve a one-year term.

She got out of prison, she went back to Nashville to this shotgun house.

She got uterine cancer and she died.

You can draw a direct line from Callie House to the reparations' movement today.

(singers vocalizing) JUSTIN HANSFORD: Marcus Garvey stepped on the scene in 1914, asking for reparations.

He created United Negro Improvement Association, the largest organization of people of African descent that has ever existed until today.

BERRY: And when his movement became more and more popular, the government decided to prosecute him.

Then when you get up to '60s, and you look at people like Malcolm X... MALCOLM X: America, the so-called land of the free.

If America gives us some land, only then will she prove she is really for freedom.

KING JR.: Now, when we come to Washington, we are coming to get our check.

♪ ♪ (singers vocalizing) ♪ Black leaves on the Mississippi River... ♪ $200 billion?

Yes, for the injury that we have received.

DANIELS: It was Queen Mother Moore who said, "You are due your reparations."

And if you see "It's Nationtime," the documentary film about the Gary Black Political Convention, you'll see Queen Mother Moore in the lobby.

This document tells you why the man owes you reparations.

This is how you've been destroyed.

JOHN CONYERS: This could be an important way to move this country into a healing mode.

SHEILA JACKSON LEE: Senator Conyers introduced H.R.

40, the commission to study slavery and develop reparations proposals, after he championed with Japanese Americans the passage of the American Civil Liberties Act signed by a Republican president, Ronald Reagan.

WOMAN: We look for major actions so that there may be a meaningful reconciliation and a healing between us and our government.

SINGER: ♪ God made woman with an iron hand ♪ ♪ Raised her up on heaven's land... ♪ Fast-forward, this is the 21st century, and African Americans, we never got repair.

COATES: While emancipation dead-bolted the door against the bandits of America, Jim Crow wedged the windows wide open.

SINGER: ♪ Black leaves on the Mississippi River ♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Black leaves in the Mississippi fire... ♪ COATES: It was 150 years ago... ...and it was right now.

The typical Black family in this country has one tenth the wealth of the typical white family, Black women die in childbirth at four times the rate of white women, and there is, of course, the shame of this "land of the free" boasting the largest prison population on the planet, of which the descendants of the enslaved make up the largest share.

SHAWN ROCHESTER: Because of what, what I call, kind of the piercing of the veil... You enjoying it.

Look at you.

Your body language displays it.

ROCHESTER: ...the country and the world saw something unfold in slow motion that they just couldn't imagine was the case.

GEORGE FLOYD: Mama, Mama, I love you.

I can't breathe.

Mama...

I can't breathe.

ROCHESTER: It provided an opportunity for white Americans and non-Black Americans to say, "Well, what can I do to make a difference?"

(loud bangs) (people screaming) GUNN: This is America's tipping point for truth-telling and reconciliation.

(cheering) We will watch this bill pass and be signed by the President of the United States of America.

(applause) GUNN: People realize it's time to start having some conversations.

LINDA MANN: We've mapped 463 efforts to attend to historical racial injustices.

Not just enslavement, but what has spanned the history of the United States.

Jim Crow, lynching, segregation.

HANSFORD: The city of Evanston, Illinois, decided that they were going to provide reparations for redlining in that city.

REPORTER: ...spending $10 million over the next ten years on reparations.

HANSFORD: 11 or 12 other cities have said that they are going to try to replicate what is happening in Evanston.

DANIELS (voiceover): It's Providence, Rhode Island, it's, it's Asheville, North Carolina, it's San Francisco, it's Detroit.

HANSFORD: California Task Force, on the state level.

MAN: California's state legislature did something no state has ever done.

It created a task force on reparations.

HANSFORD: It's much more likely that we are going to see reparations happen on a smaller level all across the country before we see it happen from the federal government's perspective.

♪ ♪ (bells chiming) LAURA MASUR: My research focuses on the archeology of Jesuit plantation sites.

When you drive around anywhere in Virginia or in Maryland, you are driving around places that were plantations.

This is the entire history of these states.

I can see it in buildings, I can see it in landscapes.

What look to be little farms, I see the slave quarters there.

It is absolutely impossible to escape the legacy of slavery once you learn to recognize it.

I came across Saint Inigoes in Newtown, owned by Jesuit priests.

These plantations are really instrumental to funding the early Catholic Church.

Um, not just the Society of Jesus, not just Jesuit institutions, they're really the foundation for Catholicism in the United States.

♪ ♪ I think what has, has made the most impact on me is realizing there's a whole history here that people didn't even know about.

HARI SREENIVASAN: More than 200 years ago, the original Georgetown College operated plantations in Maryland that worked with slave labor.

Then, in 1838, facing deep debt, a pair of priests, who each served as president of Georgetown, sold 272 people to help pay the bills.

The slaves were sent to plantations in Louisiana.

♪ ♪ Welcome to our GU272 ancestral pilgrimage tour.

Our ancestors were actually out this far.

So you see the cane fields, right?

JOSEPH STEWART: We are fifth-generation grandsons of Isaac Hawkins, the first name on the manifest of the sale of 1838.

None of us, as has been said, knew anything of that.

And since that time, I have been focused on, "Now what do you do about it?"

"The Georgetown sale was one of thousands "that forcefully migrated more than one million men, women, and children from Maryland, Virginia, and Washington D.C." ♪ ♪ STEWART: There are about 10,000 descendants, and of that number, maybe half are still living.

EARL WILLIAMS, SR.: It's personal to me.

Some of the greatest men in this country were educated in Georgetown, on our ancestors' backs.

BRANCHE-BAKER: For me, it was an opportunity to face the truth, to understand my own background and my own ancestry.

♪ ♪ STEWART: The first contact was on September 1 of 2016, when Georgetown was making an announcement about a task force report.

Throughout this past year, as the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation conducted their related efforts, they sponsor... MANN: Georgetown created a commission.

The working group completed its work over the summer.

The descendant community asked for representation on that commission.

They were denied.

Gentleman right behind you, please introduce yourself.

May I please join you?

Um, well, uh, sure.

My name is Joe Stewart, and I'm a descendant of the 272.

(applause) And I've invited other members of the 272 here to join us today.

One of the working groups said that what was missing from this scenario was the faces of the slaves.

Here are the faces.

(applause) These are the faces.

To date, we have not had the privilege in working with the working group.

You don't start reconciling by alienating.

And our attitude is "Nothing about us without us."

(applause) - Yes, I do appreciate it.

Thank you very much.

Thank you.

Appreciate it.

Then we came together around confronting the Church.

And we challenged the current leadership to make it right.

If the Church can't lead, there's nothing left in the United States, so... (voiceover): I was raised Catholic.

I'm a past altar boy.

I want to believe in my church.

Well, then, prove to me what you've been teaching me.

TIM KESICKI: And they said, "You believe in God, right?

"God wasn't there in 1838 "when you sold our ancestors, but God is here now.

What are you being called to do?"

♪ ♪ (voiceover): We have greatly sinned.

An historic truth for which we implore mercy and justice, hope and healing.

We are profoundly sorry.

♪ ♪ STEWART: That led us to the convenings... MAN: Joe, tell me about the teachers.

STEWART: ...where we had some tough and serious discussions.

But we are still just at the beginning.

MAN: The Society of Jesus enslaved up to 20,000 people.

And the sale in 1838 was the second-biggest slave sale in the 19th century.

KESICKI: We can't just say, "Well, we're sorry," and assume that that covers it.

No, we have to act.

♪ ♪ (birds chirping) DULA: There were so many things.

I found that my family probably enslaved a few thousand people over 400 years.

Another thing I discovered is that my grandmother belonged, uh, to a number of clubs, you could call them.

I did not expect was to find that she belonged to this club.

I want to be accountable for this history.

I'm not to blame for my ancestors' acts, really, of evil, and yet, I am my ancestors.

♪ ♪ Our history has been pretty well whitewashed.

Both our U.S. history or our family history.

What we usually say is, "I come from a family of hard workers.

"We bootstrapped it.

"We're so sorry that those people over there just can't seem to make it, they should just work harder."

That's the way I used to think before I actually did my research.

Now there's, there's no way I could ever make that argument again.

♪ ♪ (indistinct chatter) ♪ ♪ NORMA JOHNSON: "There comes a time when silence is betrayal."

Quote by Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

I had a deep intrinsic knowing that the path to liberation comes through the journey of what lies buried and silent in our bones.

DULA: Thank you.

We so appreciate the opportunity to speak on the topic of reparations.

So today... CUFFIE: Lotte and I are both a part of an organization called Coming to the Table, and we met at a national gathering.

They bring together descendants of enslaved folks and descendants of enslavers to heal wounds in a way.

There was a reparations meeting, and I said, "I want to start this portal.

"And it's, it's going to make white reparationists get together and do all this, blah-blah-blah."

And she just said, "You have all these high "and mighty ideas, great scholarships, all this stuff.

What do you have for me?"

CUFFIE: My proposal was paying off student loans is also arguably a way of reparations, and she was one of the people that came up after and was like, "You know, I hadn't thought about that that way.

You know, I would love to..." Her first note was, "I'd love to put $1,000 on your student loans."

And it has just literally escalated from there.

DULA: I've looked at my own family history and I've documented three different governors that were likely involved in creating the laws of slavery.

When I found out that Briayna had studied political science, that whole area, I thought, "Well, that matches the harm that I need to unwind."

For white people, one of the most important things to know is: this is not a gift.

I am repaying a debt.

CUFFIE (voiceover): I started working with Lotte.

I've learned things about my grandmother, I've learned about-- a lot about my great-grandparents, down to their personality traits and even some of the ways I stand when I take pictures.

It's, it's very creepy to see someone, you know, who's born in the 1870s have the same pose when they... when she took pictures.

DULA: Bri and I teach a class in reparative genealogy.

We really cater to white people who have a family background of enslavement, and we give them an idea of what steps you would take to begin to do repair work.

One of the first steps, understand the genesis of the racial wealth gap.

ROCHESTER: You've got Black people today in America that own about two percent of U.S. wealth.

After all of this time, about two percent.

How did we get here?

DULA: The history of my family really shows exactly how it works mechanically.

It all started with Elisha Paxton, my third great-grandfather.

He established a plantation near Lexington, Virginia, beginning around 1815.

And with the proceeds likely from the plantation operations, he was able to send many sons to law school, including my second great-grandfather.

So right there you have the benefit as education.

In the early 1830s, several of Elisha's sons, including my second great-grandfather, moved to the Mississippi Delta.

There they set up a law practice, and later multiple cotton plantations.

JACKSON LEE: Cotton became king.

Cotton drove the creation of the Wall Street banks, and made really the economy of the United States.

But where did it put African Americans?

ROCHESTER: If you go back to 1860, we know there's about four million Black people held in bondage.

Those people are the most liquid asset in the country.

22 trillion in today's value, in terms of the value of those folks to the country.

It's an enormous impact.

So the first is, what was extracted from those people during that period of time?

The second is, what was extracted from those people following that time during the Jim Crow era?

♪ ♪ CUFFIE: While Lotte is able to trace multiple of her lines back to the 1600s, most Black families hit what's called the brick wall of 1870, the first time that Black people are shown on regular census documents as free people.

So John Powell up here is my maternal great-grandfather.

He had the equivalent of a first grade education.

According to the 1940 census, just a few years before he died, John Powell Sr. was working 60 hours a week every week, all year, with an income of zero dollars.

ROCHESTER: People left bondage with no economic resources.

There was no life insurance, no salary, no workman's comp.

There was nothing.

JOHN BOYD JR.: So many Blacks stayed on those plantations and the white plantation owners said, "Okay, well, I'll set you up "with 100 acres on the low ground down by the river, and I'll take it out of the crops every year."

So that's how we were able to purchase land.

We're in my farm in Mecklenburg County, Virginia, where many of my forefathers, you know, tilled the same soil.

My grandfather bought the land from William and Ethel Boyd, white plantation owners.

So Granddaddy Thomas passed the land down to my dad, and now some, some of that very same land.

Black land ownership at the turn of the century, we were 12%-- one in every 12 farmers were Black.

And now we're down to less than one percent.

GUNN: When you talk about Black land loss to this day, it's because they were always cheated.

ROCHESTER: They need to get everything they need from the white farmer, right?

So the food, clothes, shelter, tools, everything to bring that crop to market.

When you take the crops to market, the white farmer is the market.

What they would do is make your costs higher than your revenue, so you would have a negative profit, you would owe them, and they would roll that into the following year.

And now you're in perpetual debt servitude.

And then on top of that, they have vagrancy laws that say if you can't prove that you're a landowner, and if you can't prove that you are gainfully employed, they can charge you with a criminal offense and put you in a state or county jail.

Remember, that post slavery and Jim Crow, these are very, very hostile times where Black people are being lynched on an annual basis.

GUNN: And so we had the great migration from the South to the North like, "I'm getting out of here."

That land goes away piece by piece.

But there is a distribution of land that did happen.

If you go back to 1862, Congress passes the Homestead Act.

(horse neighing) You had 246 million acres that was distributed to roughly 1.5 million white families, and what researchers say now is that up to 98 million white families are direct beneficiaries of this kind of massive economic distribution.

♪ ♪ DULA: Some of my ancestors have become millionaires receiving many, many land grants in Virginia, Mississippi, Alabama, Colorado.

JULIANNE MALVEAUX: Black people were prepared to compete, to be farmers, to be professionals, to go to law school, to run for public office.

But when Black people accumulated, white people rebelled in illegal and brutal ways.

Tulsa, Oklahoma, 1921.

It was a self-contained wealthy Black community.

The next thing you know, they were burning down Black Tulsa.

♪ ♪ There is so much pain and hurt and economic disparity.

DULA: Name a program or benefit the federal government issued, my family took advantage of it, and that's how we gained wealth.

FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT: ...to progress toward an America in which every worker will be able to provide his family at all times with an ever-rising standard of American comfort.

ROCHESTER: The New Deal established Social Security.

ANNOUNCER: Benefits will be paid to everybody who is entitled to job insurance, which does not include agricultural workers, domestic service in private homes.

Well, that's 70% of the Black labor force at that time.

The creation of the G.I.

Bill to help soldiers get training, fund college, but less than two percent of those resources went to Black people.

The government subsidizing home ownership through the F.H.A.

created the middle class.

That's a phenomenal thing, but less than one percent of all mortgages in the country went to Black people.

The other thing that was insisted on is local administration of the benefits.

Well, local administration is the most effective way to discriminate against somebody.

BOYD JR. (voiceover): Those who remained on the farm, many of us got tied up with the Farmers Home Administration.

I was 18 years of age, it's 1983, and I went up there to the Farmers home office here in Mecklenburg County, and it was almost like stepping back in time.

The county supervisor would only see Blacks one day a week, and one particular year, well, this farmer comes in-- he's white, his name was Earl.

He brought Earl into my session and he passes farmer Earl a government check for $157,000.

I was there begging for $5,000, people.

I tried nine years before I actually got a loan from them.

And you've got people talking about, "What happened to the Black farmers?"

That's what happened to us.

We didn't get access to credit when white farmers got it, pure and simple.

ROCHESTER: It's like pulling on a thread of a sweater.

There's a long continuum of discrimination that has an economic impact on Black people that makes it extraordinarily difficult for the population to accumulate wealth.

(dog barking) OFFICER: Stay down.

(talking indistinctly) OFFICER: Don't look back.

Don't look back.

DULA: We try to get people to reimagine those prosperity stories.

If your family had been Black, how would your prosperity story be different?

(woman vocalizing) ♪ ♪ (critters chirping) QUARTERMAN: I started to understand how important this land was, and land ownership for Black Americans.

EISNER: Randy and I worked to try and find attorneys to help clear title.

It was not easy, we ran into some dead ends.

Eventually a couple of really amazing folks said, "We'll take it on."

- Randy.

- Hey, good morning.

- Good to see you.

SARAH JURKIEWICZ: In order to clear title, what the court asks is that you provide all of the potential parties that may have an interest in the property.

It's a very long list of people.

I'm saying that, that one family member, would it delay the process if they say, "Hey, I need to object to this.

"This is unreasonable what you're asking me.

I'm just finding out that I'm heir to this property."

EISNER: One thing we've learned in this process is that the systems are just really set up to prevent anyone like the Quarterman family from trying to get through this process.

All of it is a learning experience.

Back then, they didn't have wills.

Lots of us don't really know all the heirs.

MICHAEL TYLER: Your next family reunion will expand exponentially.

(laughter) - Yeah.

TYLER: I think another factor is that of outright racial discrimination in terms of efforts by both private individuals, as well as governments, to actually take African American land.

♪ ♪ JOHNSON: It's a crossroads, a place where past, present, and future meet.

A place where ancestors and descendants recognize their value for each other.

(birds chirping) ♪ ♪ BRANCHE-BAKER: At this time, we speak the names of those who came before us.

Each name, we ask you to respond with "ase."

Giving us power to present not just who they are, but what they mean to us.

Hawkins.

ALL: Ase.

BRANCHE-BAKER: Hill.

ALL: Ase.

BRANCHE-BAKER: Hoppins.

ALL: Ase.

BRANCHE-BAKER: Jones.

ALL: Ase.

STEWART: We come to this place because we want the Jesuits to stand amidst the ancestors and say, "We intend to restore your dignity, but we also intend to invest in the future of our descendants."

MAN: The Society of Jesus, the Jesuits, have vowed to raise $100 million in an attempt to atone for its role in slavery here in the U.S. STEWART: This is a descendant-led vision.

At the beginning, the Jesuits' sense of what should happen was, "We can do some schools, we should do projects."

And we're saying, "No, descendants want a foundation.

Be our partner in creating a billion-dollar foundation."

That is the long-term vision, to go into dismantling the legacy of slavery.

My mom and dad both had third grade educations.

That was because they had been deprived of the equal opportunity in a nation that promised them that.

And we're still talking about those challenges.

It's time we do something.

(birds chirping) What are we up against as we undertake this sacred mission?

Yeah, I don't think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago for whom none of us currently living are responsible is a good idea.

Fear.

"What are you going to take from me?"

They want to take over what you've got, they want to control what you have.

Bull (bleep).

They are not owed that.

(cheers and applause) PAULSON: Mistrust, all too often an unwillingness to face the truth of history.

It is impossible to come up with a fair metric for recompensing slavery... - Yeah.

- ...ten generations after slavery's end.

PAULSON: A lack of faith and a lack of imagination that deep healing of racial divisions and inequalities could ever happen in many places in America.

You want total acrimony and racial strife and tension like we've never seen before, you make white folks who had nothing to do with slavery give money to Black folks... - You keep saying slavery, but you can't ignore Jim Crow.

PAULSON: They underestimate the value of the privilege of being white in the United States.

MAN: I just don't see how you could hold modern-day Americans responsible for atrocities 150 years ago.

PAULSON: How long, O Lord, how long must we live with these extreme racial disparities in these United States of America?

KESICKI: In the United States, we've never formally reconciled with slave holding, nor do we choose to remember it.

♪ ♪ I've been to Germany.

The one word they say is "remember."

Remember this happened.

♪ ♪ If we really remember it, how can we not want to respond?

BOYD JR.: Turn that camera around, look at that.

Hot damn, welcome to rural America.

Man, I'll tell you, when I talk about my history, it's offensive, nobody want to hear about slavery, but they want to hang them (bleep) damn flags up there.

(voiceover): There's always going to be a debate.

The word "reparation" scares the hell out of everybody on the Hill.

Call it something else.

Call it something else.

I never called my, my bills reparations, but that's really what it was.

(barking) WOMAN: More than one billion dollars in compensation is going out to African American farmers who faced discrimination by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

President Obama signed the settlement in 2010 and the first checks were sent out this week.

- How many times is it going to take for the United States Department of Agriculture to know that we mean business and we're not going to stop until they got off the dime and settle these cases?

I learned that what was going on in Virginia was far more egregious in Mississippi and Alabama.

Some of these guys weren't even getting applications.

So I started the National Black Farmers Association with five original members.

Today we're up to 116,000 members in 46 states.

We settled the first Black farmer case in 1999 that paid Black farmers $50,000 and 12.5 for taxes.

It's everything that fits the definition of reparations.

Apology, I got my land and I got some money.

Racism got to go!

BOYD JR.: This is many years of protesting, organizing farmers.

I'm going through a 30-year span of time here.

Not often do you see bipartisan support from both houses working together to bring fairness to Black farmers.

When you know you're right, you can't give up.

♪ ♪ (laughter, chatter) Randy, want to get in there?

(voiceover): I'm hopeful that reparations will happen on a national level, but it's going to take a long time.

We can't wait, what can we do?

And that was why Randy and I started the Quarterman-Keller Foundation, started raising from individuals, and only white people, who understand and want to redistribute wealth.

My husband Noah and I, we've been giving $100,000 a year.

This year we have ten scholars at this HPC Youth Center with Spelman, Morehouse, and Clark Atlanta.

For us to create this out of just starting off just on our heirs property is, is remarkable.

To be around these young students that are studying the history, you know, I would have never imagined.

I'm a recipient now, I can say, of personal reparation.

Nobody in our family said, "It was Zeike."

She opened that door for me, and I thank Sarah for that, asking about the property that my family never was asked or talked about.

And it surprises me because my grandfather never left.

How did we get so lost?

Every time I say I'm the fifth generation of Zeike Quarterman, an enslaved man, part of me dies.

I'm not going through that same trauma, I'm-I'm feeling healed.

I feel like it's healing me.

QUARTERMAN: When I'm even doing this work, it's tiring.

Okay?

I'm just being brutally honest.

I could just sit back and be like, "Well, Sarah, you know, "I don't want to do this no more.

I'm just going to focus on heirs property."

I could do that.

EISNER: Every day that I get Randy's participation, I'm grateful for, and any day that he-- I'm ready at any day for him to say, "I'm walking away, this is too painful."

But sometimes we just have to think outside ourselves.

Yes, we're talking about white people, what they've got to do, we already know that.

How are we holding our own selves accountable?

♪ ♪ CUFFIE: Reparations can't happen without relationships.

It shouldn't just be transactional, people should have some sort of investment and understanding why it should be done, white and Black.

♪ ♪ KESICKI: As we gather this night, we remember that we're in the month of Juneteenth.

June 19th holds another symbolic value for this group, because the sale of the 272 occurred on June 19th.

And it took 180 years for us to come together.

(laughter, chatter) We have received the beginning of their commitment to sell the plantation lands and contribute it to the Descendants Truth & Reconciliation Trust.

Can you think of the symbolism of plantation owners selling the plantation land and benefiting the people for generations to come who's suffering from what their ancestors went through?

KESICKI: The trust, now it's at just over $30 million.

So of our promise to bring in the first $100 million, that's 30%, and of the overall vision, that's only three percent.

But we can move toward an operational phase, which will help show that this partnership is bearing fruit.

STEWART: We have been doing this together now for six years.

We're frustrated, we're going too slow.

This is a long journey, but it still has not stopped progress.

♪ ♪ I told you, I packed everything.

(voiceover): I recently bought a house, and that very much has a lot to do with Lotte.

Still in Annapolis.

My ancestors have been here since before emancipation.

I am not going anywhere.

I thought, "Well, I can do housing repair.

Why not?"

MARVA HARRIS-WATSON: Have you established the proverbial junk drawer in the kitchen?

Batteries go in there, screwdrivers, whatever.

DULA: We were able to get her the resources that she needed to purchase the property.

HARRIS-WATSON: The relationship that you all have and her, um, coming into her own, it's an amazing thing to watch.

CUFFIE (voiceover): I think the personal partial reparations helps build the case for the federal government to make reparations happen at the national scale.

We're proving time and again, and in different ways and in different parts of the country, the impact it can have on people's quality of life.

What it's been able to free up for me has helped me literally be able to uplift my community in the last two years, I've been able to catalog the Black history of my town... 1841.

(voiceover): ...spend a lot more time with my elders.

My mom cries about it on a regular basis, my grandfather tells any and everyone who will listen about the work I do, and now my community pretty much does the same.

DULA (voiceover): I just want to encourage white families to do the work.

Look at your own history, come to an understanding of what kind of damages have occurred and what was your family's role?

Harm happens locally, so repair has to happen locally.

♪ ♪ WOMAN: My grandfather in the Klan... ...he and his group were personally responsible for the death of a young man and a young woman.

And I can never... bring those lives back.

♪ ♪ JOHNSON: I felt a shudder that forbade me to turn away... ...at least not without consequences.

(drum playing) (singing indistinctly) QUARTERMAN: Andrew Quarterman built this legacy, but before him there was his great-great-grandfather called Zeike Quarterman that was enslaved right around this area.

We're at the end stage to clear the title to own that land.

The government owes every Black family reparations, but for us, we just want to show that this was the beginning of our family reaching that reparations.

♪ ♪ JOHNSON: "There comes a time when silence is betrayal."

♪ ♪ In this quote, I wanted a reminder that there are consequences to my silence.

And those consequences live... in my bones.

♪ ♪ ("Black Leaves" by KIRBY playing) (vocalizing) ♪ Black leaves on the Mississippi River ♪ ♪ Black leaves in the Mississippi fire ♪ ♪ And we've got God and cotton ♪ ♪ We've got sons and daughters ♪ ♪ We've got grit and glory ♪ ♪ We've got Mama's stories ♪ ♪ We've got strength like towers ♪ ♪ We've got hope and power ♪ ♪ God made woman with an iron hand ♪ ♪ Raised her up on heaven's land ♪ ♪ God made woman with an iron hand ♪ ♪ Raised her up on heaven's land ♪ (vocalizing) ♪ ♪

The Cost of Inheritance | A Reparation of Land

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep1 | 2m 50s | Sarah Eisner's ancestor granted land to his enslaved but it was never legally given. (2m 50s)

The Cost of Inheritance | Callie House & Reparations History

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep1 | 1m 19s | The story of Callie House and her efforts to organize Black Americans for reparations. (1m 19s)

The Cost of Inheritance | Georgetown Univ. 272 Descendants

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep1 | 2m 11s | Descendants confront the truth - the Jesuits and Georgetown Univ. sold their ancestors. (2m 11s)

The Cost of Inheritance | Preview

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S12 Ep1 | 30s | Exploring reparations to illuminate the scope and rationale of this complex debate. (30s)

The Cost of Inheritance | The Wealth Gap of Black Americans

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep1 | 2m 37s | Lotte Lieb Dula and Briayna Cuffie teach Americans about repairing their family history. (2m 37s)

The Cost of Inheritance | Trailer

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S12 Ep1 | 1m | Exploring reparations to illuminate the scope and rationale of this complex debate. (1m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Funding for America ReFramed provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Wyncote Foundation and Reva and David Logan Foundation. Funding for The Cost...