Poetry in America

Phillis Wheatley: To the University

4/1/2024 | 25m 21sVideo has Closed Captions

Poems by Wheatley with Amanda Gorman, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Richard Blanco, and more.

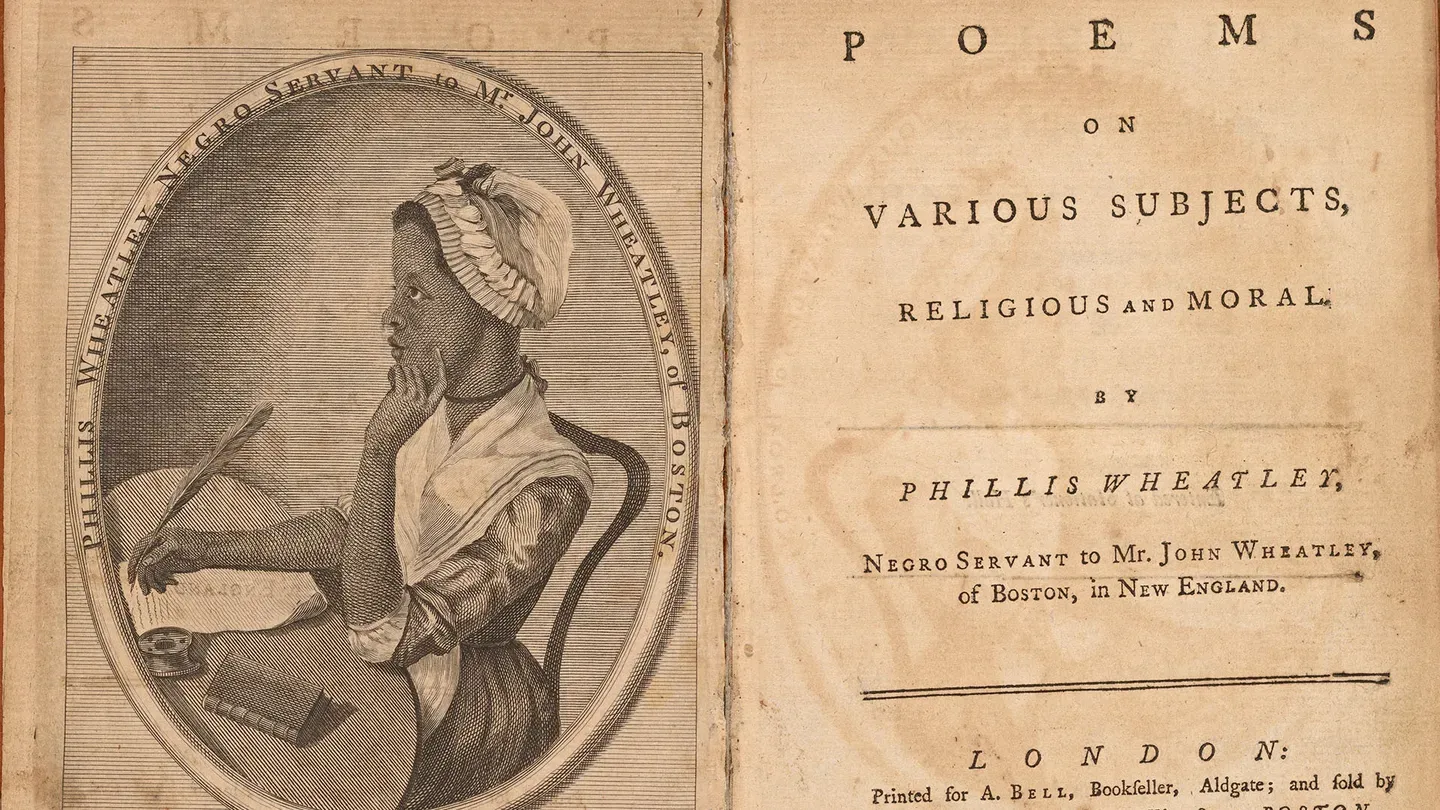

In 1770s Boston, Phillis Wheatley was at the same time enslaved and an international celebrity: a writer who mastered the most persuasive rhetoric of the day to publish enduring arguments about freedom. Inaugural poets Amanda Gorman and Richard Blanco, writer Clint Smith, and scholars Glenda Carpio and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. join host Elisa New to read two of Wheatley’s poems for public occasions.

Support for Poetry in America is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, Dalio Family Fund, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Deborah Hayes Stone and Max Stone, Nancy Zimmerman...

Poetry in America

Phillis Wheatley: To the University

4/1/2024 | 25m 21sVideo has Closed Captions

In 1770s Boston, Phillis Wheatley was at the same time enslaved and an international celebrity: a writer who mastered the most persuasive rhetoric of the day to publish enduring arguments about freedom. Inaugural poets Amanda Gorman and Richard Blanco, writer Clint Smith, and scholars Glenda Carpio and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. join host Elisa New to read two of Wheatley’s poems for public occasions.

How to Watch Poetry in America

Poetry in America is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪ -I try to imagine what it must have been like for Phillis Wheatley to disembark into Boston from her slave ship.

-This is a girl who was captured from the west coast of Africa, brought to this country -- very frail, feeble, poor health.

-She's such a young girl when she comes, she doesn't have her front teeth.

And that's how we sort of date her to being about 6 or 7 is when you lose your front teeth.

-Her name is the name of the ship, and her last name is the name of her owners.

-At what point did the family see how brilliant she was, because she was clearly a genius and a child prodigy.

-I'm very struck by the way she's not a victim of her circumstance, but rather she's almost strengthened by it.

-I want to imagine that there was a joy in what she was doing.

-She reclaims that very same language that enslaved her to use it as liberation.

-She was a revolutionary.

Phillis Wheatley is the mother of the African-American literary tradition.

♪♪ -At 17 years old, Phillis Wheatley came to international fame for a poem commemorating the death of a famous evangelist.

And five years later, she addressed a widely published poem to no less than General George Washington.

In 18th century America, poetry was everywhere, posted in public squares and printed on the front page of newspapers.

The poet's role was to give voice to broad, moral, and public values.

Just how an enslaved Black teenager stepped into this role was what I wanted to discuss with the seven interpreters I gathered to look at two poems by Wheatley, her tribute to George Washington and the one she addressed at around age 15 to the students of nearby Harvard College.

-One of the things that really pops up for me with Wheatley is the sort of unveiling of herself as a poet within the poem.

So there's kind of, like, this meta quality.

Where some poems can sound like disembodied voices, with Wheatley, I feel there's a real person there, a real person saying, "I'm writing."

-I think there's something to be said about what happens to a human when you begin to write.

And I think it's something that's spiritual, magical, divine.

-We have this ardor inside of us.

When I sit down, I invite that muse, that ardor, that passion to get to some place of discovery.

-I see an inner confidence that she has, and she says, "I have this intrinsic ardor.

This is a part of me.

But while I have this within me, while this is intrinsic, I'm also being held by this different, otherworldly force that's outside of me."

You know, the muses.

-She starts with a call to the muses, as so many poets have through centuries.

Her power is to make worlds happen.

-The Greek mythological space provides so much creativity because you see the world as it is, but then Greek mythology in some ways gives you permission to consider what different iterations of the world could be.

-Something that I learned from Phillis Wheatley is the way in which she participates in a very old and ancient tradition, and also a very Western tradition, and reclaims that as her own as an African person.

-Enslaved persons in Puritan Boston typically received treatment quite different from those in the Southern colonies or the Caribbean.

But Phillis' owner, Susanna Wheatley, was unusual.

She took the little girl under her wing and permitted her not only to read the Bible but to proceed from there to the admired writers of the day, like Alexander Pope, translator of "The Iliad."

-In the 18th century, to get admission to Harvard, speaking Greek or Latin or being able to write in it was an entrance requirement.

So she was doing the same type of rhetorical tasks which are demanded of white landed elite men.

-She's saying, "I'm learned," and maybe that's what gives her confidence, the fact that she is educated, and far more educated than most white women, let alone an enslaved African-American girl.

-Though Wheatley's poem begins in the classical world, the next lines lead us back to Scripture and to the favorite biblical story of Protestant New Englanders.

They compared their flight from religious persecution in England with the escape of enslaved Israelites from Egypt, the Exodus.

-Egypt was a symbol of slavery and also a place from which you are delivered.

-It seems to me ironic that she would be identifying with Israel emancipated when by being brought here she was enslaved.

-I think that she saw in her transportation to Massachusetts and in her proximity to the Wheatleys and Protestant Christianity, a blessing, salvation.

What is ironic, though, is that she says she is from the land of "Egyptian gloom," which is the land of Africa.

-European Christians of the 18th century used such terms as Egypt and Ethiopia to refer to the whole continent of Africa, whose inhabitants they regarded as savage and ignorant.

-"The land of errors," "Egyptian gloom."

I read it and wonder if there is something more subversive happening.

Is it a mocking of the -- you know, those -- those opinions?

-"Egyptian gloom."

-Yeah, "land of errors," "Egyptian gloom."

-Though founded in 1636 as a divinity school for the training of ministers, the Harvard College to which Wheatley addressed her poem 131 years later, was less solemn seminary than finishing school for New England's moneyed classes.

Among its students were the sons of merchants, shipbuilders, and colonial sugar planters, all active participants in and beneficiaries of the slave trade.

Just one year before Wheatley's poem and perhaps its inspiration, Harvard erupted in the Great Butter Riot.

A student uprising that began in the dining hall to protest rancid butter became a month of misrule with drunken students creating havoc in the streets.

-I think she's slightly telling off.

She's rebuking these -- these rather spoiled men, telling the frat boys, "Make the most of it.

Behave yourselves."

-She sounds to me like she deserves to be and she belongs in this university even more than the boys that she's writing to.

And maybe in a way, she's cleverly demonstrating that.

♪♪ -What Black Americans have always done is take the things that have been used as a tool or weapon of oppression... ...and have attempted to transform it into something more emancipatory.

♪♪ Enslaved Black people took Christianity and said that, "What we are experiencing here on Earth, this is a test.

And we will be rewarded after this life and God will be looking out for us when we get to heaven."

-There's absolutely no doubt that she was a deeply Christian person.

She's saying, "I'm smart enough to know that you guys are doubters, that you're skeptics, and I'm going to paint as vivid a picture as I can of our Savior to remind you that you can burn in hell for all eternity [chuckles] and instruct you."

In so many ways she was cognizant of the unique nature of her position.

-It's kind of fate that she lands with the Wheatleys.

She could have been sent to the fields, and she could have died not reading one thing.

-And I can imagine that, you know, she looks around and sees people who -- who are afforded these sorts of opportunities and take them for granted.

And it's like, "How could you?"

-"How are you able to be in this great institution with all these resources, with all of this knowledge, and you can't see a simple truth?

Your pursuit of knowledge should lead you to virtue, and you're lacking in virtue."

-If they only have knowledge but they don't have wisdom and they don't have a soul, what is it worth?

-There's no reason for her to mention her Blackness, and she wasn't from Ethiopia, but Ethiop was a metaphor for Black.

Ethiop is Greek for burnt face, and it's one of the words, like Sudan or Niger, for land of the Blacks.

But she names her Blackness there, and she is doing it to stake a claim on behalf of Black people.

-"Me and my people, we're chosen too," you know?

"We're included from the beginning of God's plan for redemption.

We are included.

We are part of this -- this great epic.

We belong here."

-Rhymed funeral elegies for public figures were the 18th century's equivalent of front-page obituaries and Wheatley's for George Whitefield propelled her to global fame.

-Phillis Wheatley is cranking out elegies all over Boston, and George Whitefield happens to die when he's in America, so she does the most famous evangelist in the world's elegy and it's a runaway bestseller and it makes her a superstar.

-Despite her growing fame, Wheatley faces widespread suspicion that she is not the author of her poems.

-There was this idea that Black people were subhuman.

Part of that inferiority was this idea that they could not create the things that were reflective of a sort of higher intellectual or emotional order.

-Well, it starts in 1753 with David Hume, and this is what he says.

"I am apt to suspect the Negroes to be naturally inferior to the whites."

Immanuel Kant takes up this issue.

"The Negroes of Africa have by nature no feeling that rises above the trifling."

-Phillis had to literally get signatories to attest to the fact that she was writing her own poems because people could not believe that she had accomplished that.

-And even the people who did believe it was her work questioned the allusions to Greek literature and Greek mythology.

"She must have just sort of copied that from somebody else.

She must have read it in another poem, and then she probably doesn't even know what it means."

-This is what I call the primal scene in Black letters, because Phillis Wheatley's book could only be published if these 18 "most respectable" characters of Boston said that she was the author.

-The tribunal determines that Phillis is the poet, and yet she is still unable to publish her book in America.

She accompanies the Wheatleys' son Nathaniel to England, hoping to find a publisher.

Abolitionists in London are clamoring to meet her.

-You can't overestimate just how important her London visit was.

It was huge.

She comes to London just one year after the famous Somerset case, the famous ruling by Lord Mansfield that James Somerset was a free man and should not be captured and taken back to Jamaica.

Huge, huge moment for the abolitionists.

-Phillis is treated like a celebrity, introduced to lords and ladies and the leaders of the abolitionist movement.

-Being in London was so formative for her because the slave trade is being debated at a very different level to what is happening in America in her hometown.

Later on, she says, "The reason I got my freedom was entirely due to my English friends."

-Returning to Boston to nurse an ailing Susanna Wheatley, Phillis arrives just in time to throw her energies into America's own struggle for independence from Britain.

In 1775, she addresses a poem to George Washington that he himself sends on to the editor of The Pennsylvania Gazette.

The poem to Washington opens in the highest epic style with the goddess of freedom, guiding and blessing the battle for America's emergence as a nation.

-I just love how she sees the world.

She sees the world as a story, an unfolding story, a narrative.

She's able to create this whole new world where she's looking down from heaven and commentating, basically.

-She calls freedom "her."

"Her anxious breast alarms."

Women goddesses are important for her.

-She's just very in tune with the divine feminine strength and power.

-Even as Wheatley's poem depicts an America smiled upon by goddesses, she also exhibits her worldly understanding of earthly geopolitics, of European powers, Britain and France contending with each other for domination of a new continent and now, of America squaring off against both.

For Wheatley, right is on America's side because its cause is freedom.

-The rhyming of "race" and "disgrace" is kind of like this little nod.

The choice of those two words, of rhyming those two words, she's saying "freedom's heaven-defended race," meaning -- you guys.

-She is saying, "I want America to be free."

But you can't help thinking she's also talking about her own freedom.

-We can't look at a word like "power" in this sort of context and not also consider the power others wield over other human beings.

-Here is an enslaved woman talking about -- this, you know, is the land of freedom.

[ Chuckles ] There's, like, an irony there that maybe she wants Washington to draw from.

"The eyes of nations."

It's not just the nations of the now, the present, right?

This, you know, "We're going to look back," just as you and I are doing now, right?

We're looking back in this moment.

It's almost like she foresaw this happening, and she's just trying to tell them, like, "They're going to look back and judge you for what you've done."

[ Chuckles ] -Part of what a poem can do is hold up a mirror to the audience.

You know, this is almost a magnifying glass.

Here are the values we share.

Look at them.

Where's the disconnect here?

-You don't have to have the genius of a philosopher to know that slavery's wrong.

Any idiot, she says, would know that slavery's an evil.

-As in classical poems addressed to kings and conquerors, Wheatley's ends with a great flourish.

Wheatley's occasional poem, addressed to the general who becomes America's first president, carves out an important role for later poets who will articulate and elevate national values on high occasions of state.

-Greeting the faces of...

The poem is, first, a conversation with yourself, but that's not necessarily being a writer.

The writer is the person who's having that conversation with themselves but knows that this conversation is going to be shared.

Millions of faces in morning's mirrors... With occasional poems, you have to even be hyperaware of audience, because it's really not just about the occasion.

It's sort of what I feel about the occasion and how can I communicate what in my heart can match the hearts of my audience?

-...move to what shall be, a country that is bruised...

Whenever I write an occasional poem, the point of emotional potency that you're trying to hit is both so small and so massive.

...aflame and unafraid...

Writing "The Hill We Climb," the inaugural poem, I was both thinking about the current, present moment that we're living in, which is so specific, but also triangulating it to other moments of grave political and national stakes.

...if only we're brave enough to see it.

If only we're brave enough to be it.

[ Applause ] -Several months after Wheatley sends her poem to the general, Washington replies.

-He writes a letter back to her, and something phenomenal happens.

He addresses her as Mrs. Phillis.

When you were addressing someone of African-American descent, you always called them by their first name.

They were always "boy," "girl," or just their first name.

And so for George Washington to be so moved by this poem that he writes not just "Miss" but "Mrs.," that means Phillis Wheatley did something fundamental with her writing, which is begin to move people's presumptions about what African-Americans were capable of being.

-Her rise was magnificent, and the descent was steep and quick.

-She remained enslaved until just before her mistress died.

-When the Revolution ends, no longer an enslaved prodigy or a symbol of abolition, and with her protector Susanna Wheatley now dead, Phillis is on her own.

She marries, works as a servant, and falls into illness and poverty.

-All that support network that ostensibly she had, and which I think some scholars have romanticized [blows] basically disappears like the head of a dandelion.

Her master left her zero in his will.

-She died penniless at 31.

-Writing, to Phillis Wheatley, was freedom.

She was doing it precisely at a moment in which our country was becoming a country in the first place.

-We're still mapping those things out, those conflicts, those nuances about ourselves as a country.

America is still a work in progress, still trying to work out what Wheatley's talking about.

-I'm very struck by the way she's able to shine in this land that she's not even born in.

She's able to say, "Well, I'm here, you brought me here, and I'm going to be excellent at this."

And I think that's very inspiring.

♪♪ ♪♪ ♪♪

Support for Poetry in America is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, Dalio Family Fund, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, Deborah Hayes Stone and Max Stone, Nancy Zimmerman...